Mountain ranges tower to the sky. Oceans plummet to impossible

depths. Earth’s surface is an amazing place to behold. Yet even the

deepest canyon is but a tiny scratch on the planet. To really understand

Earth, you need to travel 6,400 kilometers (3,977 miles) beneath our

feet.

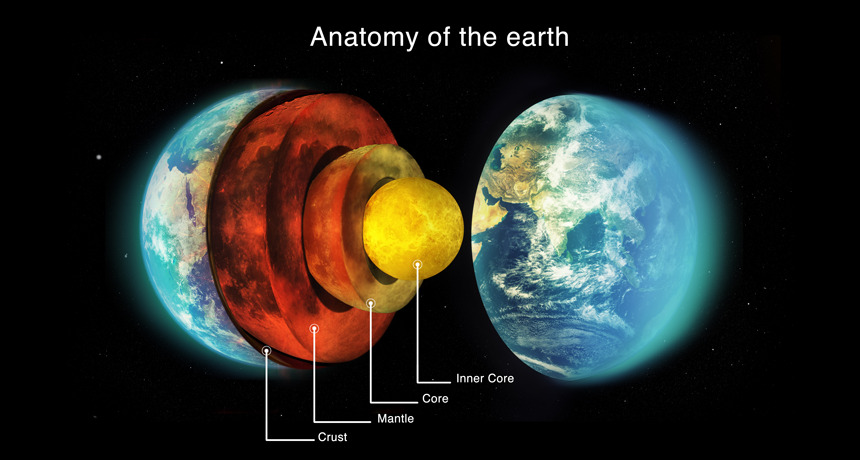

Starting at the center, Earth is composed of four distinct layers.

They are, from deepest to shallowest, the inner core, the outer core,

the mantle and the crust. Except for the crust, no one has ever explored

these layers in person. In fact, the deepest humans have ever drilled

is just over 12 kilometers (7.6 miles). And even that took 20 years!

Still, scientists know a great deal about Earth’s inner structure.

They’ve plumbed it by studying how earthquake waves travel through the

planet. The speed and behavior of these waves change as they encounter

layers of different densities. Scientists — including Isaac Newton,

three centuries ago — have also learned about the core and mantle from

calculations of Earth’s total density, gravitational pull and magnetic

field.

Here’s a primer on Earth’s layers, starting with a journey to the center of the planet.

A cut-away of Earth’s layers reveals how thin the crust is when compared to the lower layers.USGS

The inner core

This solid metal ball has a radius of 1,220 kilometers (758 miles),

or about three-quarters that of the moon. It’s located some 6,400 to

5,180 kilometers (4,000 to 3,220 miles) beneath Earth’s surface.

Extremely dense, it’s made mostly of iron and nickel. The inner core

spins a bit faster than the rest of the planet. It’s also intensely hot:

Temperatures sizzle at 5,400° Celsius (9,800° Fahrenheit). That’s

almost as hot as the surface of the sun. Pressures here are immense:

well over 3 million times greater than on Earth’s surface. Some research

suggests there may also be an inner, inner core. It would likely

consist almost entirely of iron.

The outer core

This part of the core is also made from iron and nickel, just in

liquid form. It sits some 5,180 to 2,880 kilometers (3,220 to 1,790

miles) below the surface. Heated largely by the radioactive decay of the

elements uranium and thorium, this liquid churns in huge, turbulent

currents. That motion generates electrical currents. They, in turn,

generate Earth’s magnetic field. For reasons somehow related to the

outer core, Earth’s magnetic field reverses about every 200,000 to

300,000 years. Scientists are still working to understand how that

happens.

The mantle

At close to 3,000 kilometers (1,865 miles) thick, this is Earth’s

thickest layer. It starts a mere 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) beneath the

surface. Made mostly of iron, magnesium and silicon, it is dense,

hot and semi-solid (think caramel candy). Like the layer below it, this

one also circulates. It just does so far more slowly.

Near its upper edges, somewhere between about 100 and 200 kilometers

(62 to 124 miles) underground, the mantle’s temperature reaches the

melting point of rock. Indeed, it forms a layer of partially melted rock

known as the asthenosphere (As-THEEN-oh-sfeer). Geologists believe this

weak, hot, slippery part of the mantle is what Earth’s tectonic plates

ride upon and slide across.

Diamonds are tiny pieces of the mantle we can actually touch. Most form at depths above 200 kilometers (124 miles). But rare “super-deep” diamonds

may have formed as far down as 700 kilometers (435 miles) below the

surface. These crystals are then brought to the surface in volcanic rock

known as kimberlite.

The mantle’s outermost zone is relatively cool and rigid. It behaves

more like the crust above it. Together, this uppermost part of the

mantle layer and the crust are known as the lithosphere.

The thickest part of Earth’s crust is about 70 kilometers (43 miles) thick and lies under the Himalayan Mountains, seen here.den-belitsky/iStock/Getty Images Plus

The crust

Earth’s crust is like the shell of a hard-boiled egg. It is extremely

thin, cold and brittle compared to what lies below it. The crust is

made of relatively light elements, especially silica, aluminum and

oxygen. It’s also highly variable in its thickness. Under the oceans

(and Hawaiian Islands), it may be as little as 5 kilometers (3.1 miles)

thick. Beneath the continents, the crust may be 30 to 70 kilometers

(18.6 to 43.5 miles) thick.

Along with the upper zone of the mantle, the crust is broken into big pieces, like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle. These are known as tectonic plates.

These move slowly — at just 3 to 5 centimeters (1.2 to 2 inches) per

year. What drives the motion of tectonic plates is still not fully

understood. It may be related to heat-driven convection currents in the

mantle below. Some scientists think it’s caused by the tug from slabs of

crust of different densities, something called “slab pull.” In time,

these plates will converge, pull apart or slide past each other. Those

actions cause most earthquakes and volcanoes. It’s a slow ride, but it

makes for exciting times here on Earth’s surface.

.jpg)