Esther Before Ahasuerus

Purim

Artemisia Gentileschi

(Italian, born Rome 1593–died Naples 1654)

The most famous woman painter of the seventeenth century, Artemisia

worked in Rome, Florence, Venice, and Naples.

This painting, among her

most ambitious, recounts the story of the Jewish heroine Esther, who

appeared before King Ahasuerus to plead for her people, breaking with

court etiquette and risking death. She fainted in the king’s presence,

but her request found favor.

The story is conceived not as a historical

recreation but as a contemporary theatrical performance.

Initially

Artemisia included the detail of a black boy restraining a dog - still

partly visible beneath the marble pavement, to the left of Ahasuerus’s

knee.

The Artist:

Artemisia Gentileschi is the most famous female

artist of the seventeenth century. Earlier painters, such as Sofonisba

Anguissola of Cremona (ca. 1532–1625) and Lavinia Fontana of Bologna

(1552–1614), earned reputations based on portraiture and devotional

paintings, while Fede Galizia (1578–1630) was celebrated for her still

lifes.

Artemisia was the first woman artist to gain a reputation as an

accomplished painter of large, multi-figure compositions with a

mythological or Biblical theme - the sort of work considered the most

demanding test of an artist’s ability.

Her pictures often have violent

themes with female protagonists and, rightly or wrongly, these have

often been related to her biography.

She was trained in Rome by her

father, Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639) - one of the earliest followers of

Caravaggio - and in 1611 was raped by an artist (Agostino Tassi) her father

had engaged to teach her perspective. A trial ensued, and in 1612 she

was married off to a minor painter (Piermatteo Stiattesi) and moved to

Florence. There she established her reputation at the court of Grand

Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici; associated with the literary and artistic

circle around the poet Michelangelo Buonarroti the younger; and in 1616

became the first female member of the Accademia del Disegno - an

extraordinary accomplishment for someone who, in Rome, had been a

self-declared illiterate (on this transformation, see Keith

Christiansen, "Becoming Artemisia: Afterthoughts on the Gentileschi

Exhibition," Metropolitan Museum Journal 39 (2004), pp. 101–26).

Her peripatetic later career took her back to Rome (1620–26), Venice

(1626–30), and Naples (1630–52), with a brief trip to London, where she

seems again to have worked with her father (1634).

Her reevaluation as a

major figure in the history of European painting got under way with a

fictional biography by Anna Banti in 1947 (translated into English in

1988). Among the most interesting documents to have emerged is a cache

of love letters addressed to the Florentine nobleman Francesco Maria di

Niccolò Maringhi, published in 2011 by Francesco Solinas. Locker’s book

(2015), the findings of which are directly relevant to the painting in

The Met, adds a further dimension to her biography by investigating her

involvement with the literary culture of Venice and Naples.

In many

ways, the history of The Met’s picture maps out the transformation of

awareness of Artemisia’s stature. Prior to Herman Voss’s recognition of

her authorship in 1924, when the painting was in the famed Harrach

collection in Vienna, it had, incredibly, been ascribed to El Greco and

Benedetto Genari!

It remains one of her most ambitious compositions.

The Picture:

The Picture:

The Old Testament book of Esther recounts how the beautiful young

Esther interceded with the Persian king Ahasuerus to spare the Jews.

When Ahasuerus's wife Vashti offended him, he replaced her with Esther,

not knowing she was Jewish. After a decree went out that all the Jews in

the Persian empire should be massacred, Esther intervened on behalf of

her people, even though to enter the king's presence without being

summoned was forbidden on pain of death. Swooning with fear, she

confronted the king, who received her and granted her request.

Artemisia's

imagery closely follows the text of Greek additions made to the

original Hebrew narrative, popularly used in the seventeenth century,

after the Council of Trent gave them canonical status in 1546:

"On the third day, when she had finished praying, she took off her supplicant's mourning attire and dressed herself in her full splendor. Radiant as she then appeared, she invoked God who watches over all people and saves them. With her, she took her two ladies-in-waiting. With a delicate air she leaned on one, while the other accompanied her carrying her train. Rosy wtih the full flush of her beauty, her face radiated joy and love: but her heart shrank with fear. Having passed through door after door, she found herself in the presence of the king. He was sitting on his royal throne, dressed in all his robes of state, glittering with gold and precious stones - a formidable sight. He looked up, afire with majesty and, blazing with anger, saw her. The queen sank to the floor. As she fainted, the color drained from her face and her head fell against the lady-in-waiting beside her. But God changed the king's heart, inducing a milder spirit. He sprang from his throne in alarm and took her in his arms until she recovered, comforting her with soothing words. 'What is the matter Esther?' he said. 'I am your brother. Take heart, you are not going to die; our order applies only to ordinary people. Come to me.' And raising his golden sceptre he laid it on Esther's neck, embraced her and said, 'Speak to me.'"

As recognized by a number of scholars (Garrard 1989, Bissell 1999, Locker 2015) Artemisia's composition is closely related to that of a version of the subject from the workshop of Paolo Veronese (Musée du Louvre, Paris; see below).

"On the third day, when she had finished praying, she took off her supplicant's mourning attire and dressed herself in her full splendor. Radiant as she then appeared, she invoked God who watches over all people and saves them. With her, she took her two ladies-in-waiting. With a delicate air she leaned on one, while the other accompanied her carrying her train. Rosy wtih the full flush of her beauty, her face radiated joy and love: but her heart shrank with fear. Having passed through door after door, she found herself in the presence of the king. He was sitting on his royal throne, dressed in all his robes of state, glittering with gold and precious stones - a formidable sight. He looked up, afire with majesty and, blazing with anger, saw her. The queen sank to the floor. As she fainted, the color drained from her face and her head fell against the lady-in-waiting beside her. But God changed the king's heart, inducing a milder spirit. He sprang from his throne in alarm and took her in his arms until she recovered, comforting her with soothing words. 'What is the matter Esther?' he said. 'I am your brother. Take heart, you are not going to die; our order applies only to ordinary people. Come to me.' And raising his golden sceptre he laid it on Esther's neck, embraced her and said, 'Speak to me.'"

As recognized by a number of scholars (Garrard 1989, Bissell 1999, Locker 2015) Artemisia's composition is closely related to that of a version of the subject from the workshop of Paolo Veronese (Musée du Louvre, Paris; see below).

Artemisia, whose sojourn in Venice between

1626 and 1630 has assumed greater importance in recent studies, must

have been familiar with Veronese’s canvas, which was in a private

collection there until 1662. Indeed, certain details of her composition

seem to depend directly from it, including the close proximity of the

heads of Esther and one of her maids, the configuration and position of

Esther's left hand, and the circular dais of Ahasuerus’s throne. As

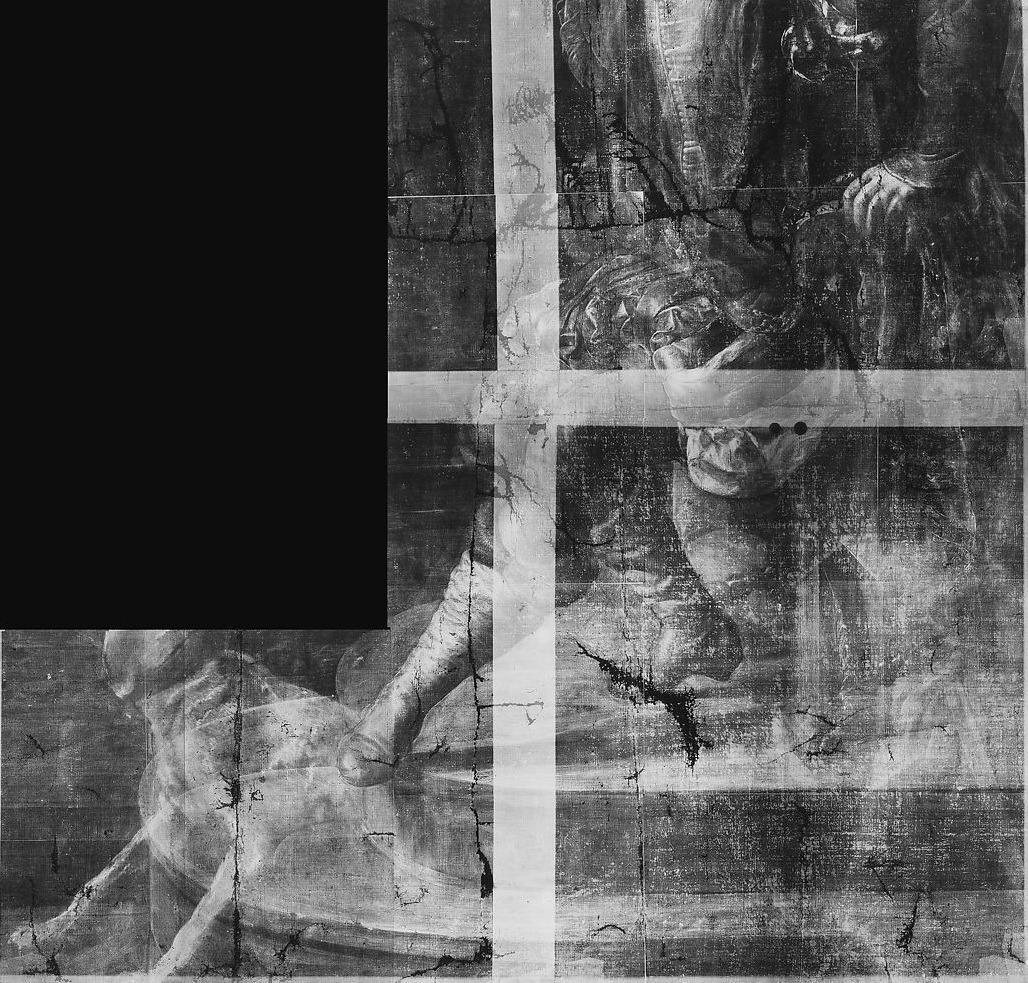

revealed in an x-ray (fig. 2), Artemisia initially painted an African

boy restraining a dog—another motif interpolated from Veronese’s work,

in which a dwarf and dog appear, though the dog is resting rather than

growling at the queen in the Veronese composition.

Although most scholars (Voss 1924, Kaufmann 1970, Contini 1991) have placed the Esther Before Ahasuerus in Artemisia's first Neapolitan period—that is, in the 1630s—Garrard (1989) originally assigned the painting to Artemisia's Roman period of the early 1620s, based on what she saw as the overtly Caravaggesque garb of King Ahasuerus and on her assumption that Artemisia saw the Veronese-school Esther during a Venetian trip in the early 1620s. Later (2001), she changed her dating to about 1630, and like Bissell (1999) and Contini (1991) saw in the handling of light and costumes a renewed acquaintance with Tuscan sources, most probably the work of the Sienese Caravaggesque painter Rutilio Manetti (ca. 1571–1639). Building on this evidence, Locker (2015) has examined the picture in light of what we now know about Artemisia’s presence in Venice and her association with a circle of people who formed an informal literary academy, the Accademia de’ Desiosi, as well as the better-documented Accademia degli Incogniti. Among the topics discussed in the latter was the place and nature of women. Unusually, women participated in this discussion, including the Venetian author/poet Lucrezia Marinella (ca. 1571–1653), who wrote a treatise entitled La Nobiltà et l'eccellenza delle donne, co' diffetti e mancamenti de gli huomini (The nobility and excellence of women, and the defects and vices of men). Locker has suggested that Artemisia’s painting should be seen as a visual contribution to this debate—painted towards the end of her Venetian sojourn.

In most treatments of the story, Ahasuerus is shown sitting on an elevated throne, regally garbed and holding a scepter. By contrast, Artemisia shows him foppishly dressed, wearing an extravagantly feathered hat and crown, slashed sleeves, and fur-trimmed, jeweled boots.

Although most scholars (Voss 1924, Kaufmann 1970, Contini 1991) have placed the Esther Before Ahasuerus in Artemisia's first Neapolitan period—that is, in the 1630s—Garrard (1989) originally assigned the painting to Artemisia's Roman period of the early 1620s, based on what she saw as the overtly Caravaggesque garb of King Ahasuerus and on her assumption that Artemisia saw the Veronese-school Esther during a Venetian trip in the early 1620s. Later (2001), she changed her dating to about 1630, and like Bissell (1999) and Contini (1991) saw in the handling of light and costumes a renewed acquaintance with Tuscan sources, most probably the work of the Sienese Caravaggesque painter Rutilio Manetti (ca. 1571–1639). Building on this evidence, Locker (2015) has examined the picture in light of what we now know about Artemisia’s presence in Venice and her association with a circle of people who formed an informal literary academy, the Accademia de’ Desiosi, as well as the better-documented Accademia degli Incogniti. Among the topics discussed in the latter was the place and nature of women. Unusually, women participated in this discussion, including the Venetian author/poet Lucrezia Marinella (ca. 1571–1653), who wrote a treatise entitled La Nobiltà et l'eccellenza delle donne, co' diffetti e mancamenti de gli huomini (The nobility and excellence of women, and the defects and vices of men). Locker has suggested that Artemisia’s painting should be seen as a visual contribution to this debate—painted towards the end of her Venetian sojourn.

In most treatments of the story, Ahasuerus is shown sitting on an elevated throne, regally garbed and holding a scepter. By contrast, Artemisia shows him foppishly dressed, wearing an extravagantly feathered hat and crown, slashed sleeves, and fur-trimmed, jeweled boots.

Locker has noted that the parallels for this kind of

dress are to be found on the stage, where it is invariably associated

with a comedic character, and further, that by this parodic treatment

Artemisia emphasized the superiority of Esther and, by extension, of

women as rulers.

His interpretation adds a new dimension to the Feminist

discussion of this picture and of Artemisia’s work in general by

situating it within the intellectual and cultural world of Seicento

Italy.

Keith Christiansen

Keith Christiansen

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 637

The Humble Story of Esther & Her Cousin Mordecai

Bible Stories

👇 📺 👇

👇 📺 👇

No comments:

Post a Comment