🎼 Opéra Français 🇫🇷

🇫🇷 French Opéra 🎼

🇫🇷 French Opéra 🎼

French Opéra is one of Europe's most important operatic traditions, containing works by composers of the stature of Rameau, Berlioz, Gounod, Bizet, Massenet, Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc and Messiaen. Many foreign-born composers have played a part in the French tradition as well, including Lully, Gluck, Salieri, Cherubini, Spontini, Meyerbeer, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi and Offenbach.

French opera began at the court of Louis XIV of France with Jean-Baptiste Lully's Cadmus et Hermione (1673), although there had been various experiments with the form before that, most notably Pomone by Robert Cambert. Lully and his librettist Quinault created tragédie en musique, a form in which dance music and choral writing were particularly prominent. Lully's most important successor was Rameau.

After Rameau's death, the German Gluck was persuaded to produce six operas for the Parisian stage in the 1770s. They show the influence of Rameau, but simplified and with greater focus on the drama. At the same time, by the middle of the 18th century another genre was gaining popularity in France: opéra comique, in which arias alternated with spoken dialogue. By the 1820s, Gluckian influence in France had given way to a taste for the operas of Rossini. Rossini's Guillaume Tell helped found the new genre of Grand opera, a form whose most famous exponent was Giacomo Meyerbeer. Lighter opéra comique also enjoyed tremendous success in the hands of Boïeldieu, Auber, Hérold and Adam. In this climate, the operas of the French-born composer Hector Berlioz struggled to gain a hearing. Berlioz's epic masterpiece Les Troyens, the culmination of the Gluckian tradition, was not given a full performance for almost a hundred years after it was written.

Opéra 🎼 Français 🇫🇷 French ⚜️ Opéra 🐓

Click  "CC" To Translate

"CC" To Translate

In the second half of the 19th century, Jacques Offenbach dominated the new genre of operetta with witty and cynical works such as Orphée aux enfers; Charles Gounod scored a massive success with Faust; and Georges Bizet composed Carmen, probably the most famous French opera of all. At the same time, the influence of Richard Wagner was felt as a challenge to the French tradition. Perhaps the most interesting response to Wagnerian influence was Claude Debussy's unique operatic masterpiece Pelléas et Mélisande (1902). Other notable 20th-century names include Ravel, Poulenc and Messiaen.

The Birth of French Opéra: Lully

The first operas to be staged in France were imported from Italy, beginning with Francesco Sacrati's La finta pazza in 1645. French audiences gave them a lukewarm reception. This was partly for political reasons, since these operas were promoted by the Italian-born Cardinal Mazarin, who was then first minister during the regency of the young King Louis XIV and a deeply unpopular figure with large sections of French society. Musical considerations also played a role, since the French court already had a firmly established genre of stage music, ballet de cour, which included sung elements as well as dance and lavish spectacle. When two Italian operas, Francesco Cavalli's Xerse and Ercole amante, proved failures in Paris in 1660 and 1662, the prospects of opera flourishing in France looked remote. Yet Italian opera would stimulate the French to make their own experiments at the genre and, paradoxically, it would be an Italian-born composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully, who would found a lasting French operatic tradition.

Jean-Baptiste Lully "Father of French Opera"

⚜️ The music of the Ancien Régime 👑

Jean-Baptiste Lully 🎼 Louis XIV 👑 Louis XV 👑 Louis XVI ⚜️

Jean-Baptiste Lully 🎼 Louis XIV 👑 Louis XV 👑 Louis XVI ⚜️

A tribute to the old French regime, and to the reigns of their majesties Kings Louis XIV, Louis XV and Louis XVI, through the beautiful compositions of master Jean-Baptiste Lully, symbol of French baroque music!

https://youtu.be/J-Hk5lJbjkU?si=_AdTyN5EuDiY1ZbK

In 1669, Pierre Perrin founded the Académie d'Opéra and, in collaboration with the composer Robert Cambert, tried his hand at composing operatic works in French. Their first effort, Pomone, appeared on stage on 3 March 1671 and was followed a year later by Les peines et plaisirs de l'amour. At this point King Louis XIV transferred the privilege of producing operas from Perrin to Jean-Baptiste Lully. Lully, a Florentine, was already the favorite musician of the king, who had assumed full royal powers in 1661 and was intent on refashioning French culture in his image. Lully had a sure instinct for knowing exactly what would satisfy the taste of his master and the French public in general. He had already composed music for extravagant court entertainments as well as for the theatre, most notably the comédies-ballets inserted into plays by Molière. Yet Molière and Lully had quarrelled bitterly and the composer found a new and more pliable collaborator in Philippe Quinault, who would write the libretti for all but two of Lully's operas. On 27 April 1673, Lully's Cadmus et Hermione – often regarded as the first French opera in the full sense of the term – appeared in Paris. It was a work in a new genre, which its creators Lully and Quinault baptised tragédie en musique, a form of opera specially adapted for French taste. Lully went on to produce tragédies en musique at the rate of at least one a year until his death in 1687 and they formed the bedrock of the French national operatic tradition for almost a century. As the name suggests, tragédie en musique was modelled on the French Classical tragedy of Corneille and Racine. Lully and Quinault replaced the confusingly elaborate Baroque plots favoured by the Italians with a much clearer five-act structure. Each of the five acts generally followed a regular pattern. An aria in which one of the protagonists expresses their inner feelings is followed by recitative mixed with short arias (petits airs) which move the action forward. Acts end with a divertissement, the most striking feature of French Baroque opera, which allowed the composer to satisfy the public's love of dance, huge choruses and gorgeous visual spectacle. The recitative, too, was adapted and moulded to the unique rhythms of the French language and was often singled out for special praise by critics, a famous example occurring in Act Two of Lully's Armide. The five acts of the main opera were preceded by an allegorical prologue, another feature Lully took from the Italians, which he generally used to sing the praises of Louis XIV. Indeed, the entire opera was often thinly disguised flattery of the French monarch, who was represented by the noble heroes drawn from Classical myth or Mediaeval romance. The tragédie en musique was a form in which all the arts, not just music, played a crucial role. Quinault's verse combined with the set designs of Carlo Vigarani or Jean Bérain and the choreography of Beauchamp and Olivet, as well as the elaborate stage effects known as the machinery. As one of its detractors, Melchior Grimm, was forced to admit: "To judge of it, it is not enough to see it on paper and read the score; one must have seen the picture on the stage".

Gluck in Paris

While opéra comique flourished in the 1760s, serious French opera was in the doldrums. Rameau had died in 1764, leaving his last great tragédie en musique, Les Boréades unperformed. No French composer seemed capable of assuming his mantle. The answer was to import a leading figure from abroad. Christoph Willibald von Gluck, a German, was already famous for his reforms of Italian opera, which had replaced the old opera seria with a much more dramatic and direct style of music theatre, beginning with Orfeo ed Euridice in 1762. Gluck admired French opera and had absorbed the lessons of both Rameau and Rousseau. In 1765, Melchior Grimm published "Poème lyrique", an influential article for the Encyclopédie on lyric and opera librettos. Under the patronage of his former music pupil, Marie Antoinette, who had married the future French king Louis XVI in 1770, Gluck signed a contract for six stage works with the management of the Paris Opéra. He began with Iphigénie en Aulide (19 April 1774). The premiere sparked a huge controversy, almost a war, such as had not been seen in the city since the Querelle des Bouffons. Gluck's opponents brought the leading Italian composer, Niccolò Piccinni, to Paris to demonstrate the superiority of Neapolitan opera and the "whole town" engaged in an argument between "Gluckists" and "Piccinnists".

On 2 August 1774, the French version of Orfeo ed Euridice was performed, with the title role transposed from the castrato to the

haute-contre, according to the French preference for high tenor voices which had ruled since the days of Lully. This time Gluck's work was better received by the Parisian public. Gluck went on to write a revised French version of his Alceste, as well as the new works Armide (1777), Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) and Echo et Narcisse for Paris. After the failure of the last named opera, Gluck left Paris and retired from composing. But he left behind an immense influence on French music and several other foreign composers followed his example and came to Paris to write

Gluckian operas, including Salieri (Les Danaïdes, 1784) and Sacchini (Oedipe à Colone, 1786).

Louis XIV ⚜️ Ballet de la Nuit 1653

From the Revolution to Rossini

The French Revolution of 1789 was a cultural watershed. What was left of the old tradition of Lully and Rameau was finally swept away, to be rediscovered only in the twentieth century. The Gluckian school and opéra comique survived, but they immediately began to reflect the turbulent events around them. Established composers such as Grétry and Dalayrac were drafted in to write patriotic propaganda pieces for the new regime. A typical example is Gossec's Le triomphe de la République (1793) which celebrated the crucial Battle of Valmy the previous year. A new generation of composers appeared, led by Étienne Méhul and the Italian-born Luigi Cherubini. They applied Gluck's principles to opéra comique,

giving the genre a new dramatic seriousness and musical sophistication.

The stormy passions of Méhul's operas of the 1790s, such as Stratonice and Ariodant, earned their composer the title of the first musical Romantic. Cherubini's works too held a mirror to the times. Lodoiska was a "rescue opera" set in Poland, in which the imprisoned heroine is freed and her oppressor overthrown. Cherubini's masterpiece, Médée

(1797), reflected the bloodshed of the Revolution only too successfully: it was always more popular abroad than in France. The lighter Les deux journées of 1800 was part of a new mood of reconciliation in the country.

Theatres had proliferated during the 1790s, but when Napoleon took power, he simplified matters by effectively reducing the number of Parisian opera houses to three. These were the Opéra (for serious operas with recitative not dialogue); the Opéra-Comique (for works with spoken dialogue in French); and the Théâtre-Italien (for imported Italian operas). All three would play a leading role over the next half-century or so. At the Opéra, Gaspare Spontini upheld the serious Gluckian tradition with La Vestale (1807) and Fernand Cortez (1809). Nevertheless, the lighter new opéra-comiques of Boieldieu and Isouard were a bigger hit with French audiences, who also flocked to the Théâtre-Italien to see traditional opera buffa and works in the newly fashionable bel canto style, especially those by Rossini, whose fame was sweeping across Europe. Rossini's influence began to pervade French opéra comique. Its presence is felt in Boieldieu's greatest success, La dame blanche (1825) as well as later works by Auber (Fra Diavolo, 1830; Le domino noir, 1837), Hérold (Zampa, 1831) and Adolphe Adam (Le postillon de Longjumeau, 1836). In 1823, the Théâtre-Italien scored an immense coup when it persuaded Rossini himself to come to Paris and take up the post of manager of the opera house. Rossini arrived to welcome worthy of a modern media celebrity. Not only did he revive the flagging fortunes of the Théâtre-Italien, but he also turned his attention to the Opéra, giving

it French versions of his Italian operas and a new piece, Guillaume Tell (1829). This proved to be Rossini's final work for the stage. Ground down by the excessive workload of running a theatre and disillusioned by

the failure of Tell, Rossini retired as an opera composer.

Grand Opera

Guillaume Tell might initially have been a failure but together with a work from the previous year, Auber's La muette de Portici, it ushered in a new genre which dominated the French stage for the rest of the century: grand opera.

This was a style of opera characterised by grandiose scale, heroic and historical subjects, large casts, vast orchestras, richly detailed sets, sumptuous costumes, spectacular scenic effects and – this being France – a great deal of ballet music. Grand opera had already been prefigured by works such as Spontini's La vestale and Cherubini's Les Abencérages (1813), but the composer history has above all come to associate with the genre is Giacomo Meyerbeer. Like Gluck, Meyerbeer was a German who had learnt his trade composing

Italian opera before arriving in Paris. His first work for the Opéra, Robert le diable (1831), was a sensation; audiences particularly thrilled to the ballet sequence in Act Three in which the ghosts of corrupted nuns rise from their graves. Robert, together with Meyerbeer's three subsequent grand operas, Les Huguenots (1836), Le prophète (1849) and L'Africaine (1865), became part of the repertoire throughout Europe for the rest of the nineteenth century and exerted an immense influence on other composers, even though the musical merit of these extravagant works was often disputed. In fact, the most famous example of French grand opera likely to be encountered in opera houses today is by Giuseppe Verdi, who wrote Don Carlos for the Paris Opéra in 1867.

Berlioz

While Meyerbeer's popularity has faded, the fortunes of another French

composer of the era have risen steeply over the past few decades. Yet the operas of Hector Berlioz were failures in their day. Berlioz was a unique mixture of an innovative modernist and a backward-looking conservative. His taste in opera had been formed in the 1820s, when the works of Gluck and his followers were being pushed aside in favour of Rossinian bel canto. Though Berlioz grudgingly admired some works by Rossini, he despised what he saw as the showy effects of the Italian style and longed to

return opera to the dramatic truth of Gluck. He was also a fully-fledged Romantic, keen to find new ways of musical expression. His first and only work for the Paris Opéra, Benvenuto Cellini (1838), was a notorious failure. Audiences could not understand the opera's originality and musicians found its unconventional rhythms impossible to play. Twenty years later, Berlioz began writing his operatic masterpiece Les Troyens with himself rather than audiences of the day in mind. Les Troyens was to be the culmination of the French Classical tradition of Gluck and Spontini. Predictably, it failed to make the stage, at least in its complete, four-hour form. For that, it would have to wait until the

second half of the twentieth century, fulfilling the composer's prophecy, "If only I could live till I am a hundred and forty, my life would become decidedly interesting". Berlioz's third and final opera, the Shakespearean comedy Béatrice et Bénédict (1862), was written for a theatre in Germany, where audiences were far more appreciative of his musical innovation.

The late 19th century

Berlioz was not the only one discontented with operatic life in Paris. In the 1850s, two new theatres attempted to break the monopoly of the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique on the performance of musical drama in the capital. The Théâtre Lyrique ran from 1851 to 1870. It was here in 1863 that Berlioz saw the only part of Les Troyens to be performed in his lifetime. But the Lyrique also staged the premieres of works by a rising new generation of French opera composers,

led by Charles Gounod and Georges Bizet. Though not as innovative as Berlioz, these composers were receptive to new musical influences. They also liked writing operas on literary themes. Gounod's Faust (1859), based on the drama by Goethe, became an enormous worldwide success. Gounod followed it with Mireille (1864), based on the Provençal epic by Frédéric Mistral, and the Shakespeare-inspired Roméo et Juliette (1867). Bizet offered the Théâtre Lyrique Les pêcheurs de perles (1863) and La jolie fille de Perth, but his biggest triumph was written for the Opéra-Comique. Carmen

(1875) is now perhaps the most famous of all French operas. Early critics and audiences, however, were shocked by its unconventional blend of romantic passion and realism.

Another figure unhappy with the Parisian operatic scene in the mid-nineteenth century was Jacques Offenbach. He found that contemporary French opéra-comiques no longer offered any room for comedy. His little theatre the Bouffes-Parisiens, established in 1855, put on short one-act pieces full of farce and satire. In 1858, Offenbach tried something more ambitious. Orphée aux enfers ("Orpheus in the Underworld") was the first work in a new genre: operetta. Orphée

was both a parody of highflown Classical tragedy and a satire on contemporary society. Its incredible popularity prompted Offenbach to follow up with more operettas such as La belle Hélène (1864) and La Vie parisienne (1866) as well as the more serious Les contes d'Hoffmann (1881).

Opera flourished in late nineteenth-century Paris and many works

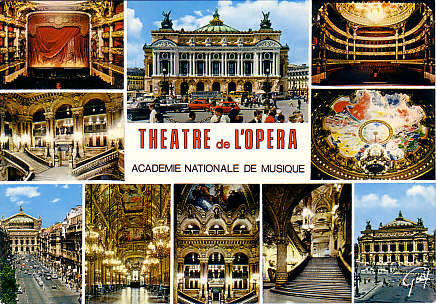

of the period went on to gain international renown. These include Mignon (1866) and Hamlet (1868) by Ambroise Thomas; Samson et Dalila (1877, in the Opéra's new home, the Palais Garnier) by Camille Saint-Saëns; Lakmé (1883) by Léo Delibes; and Le roi d'Ys (1888) by Édouard Lalo. The most consistently successful composer of the era was Jules Massenet, who produced twenty-five operas in his characteristically suave and elegant style, including several for the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels and the Opéra de Monte-Carlo. His tragic romances Manon (1884) and Werther (1892) have weathered changes in musical fashion and are still widely performed today.

Opera National de Paris - Opéra Bastille. Inaugurated in 1989

A modern opera house in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, France.

Contents

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment