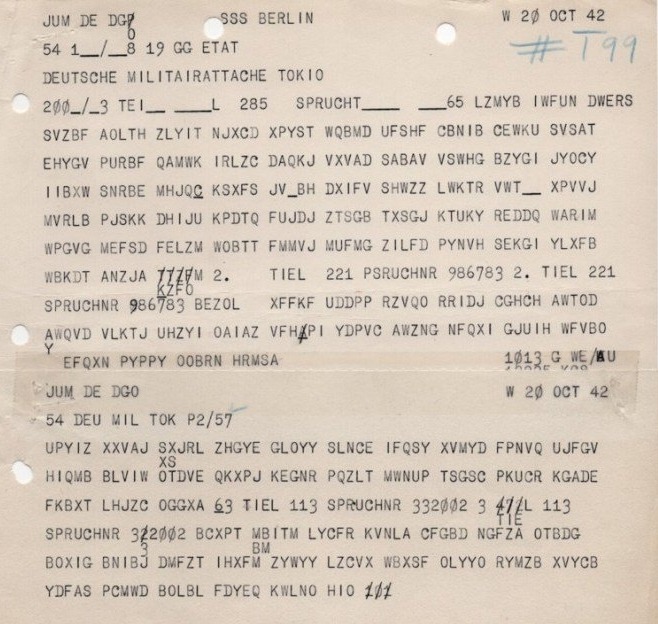

And so the young women did their strange new homework. They learned which letters of the English language occur with the greatest frequency; which letters often travel together in pairs, like s and t; which travel in triplets, like est and ing and ive, or in packs of four, like tion. They studied terms like “route transposition” and “cipher alphabets” and “polyalphabetic substitution cipher.” They mastered the Vigenère square, a method of disguising letters using a tabular method dating back to the Renaissance. They learned about things called the Playfair and Wheatstone ciphers. They pulled strips of paper through holes cut in cardboard. They strung quilts across their rooms so that roommates who had not been invited to take the secret course could not see what they were up to. They hid homework under desk blotters. They did not use the term “code breaking” outside the confines of the weekly meetings, not even to friends taking the same course.

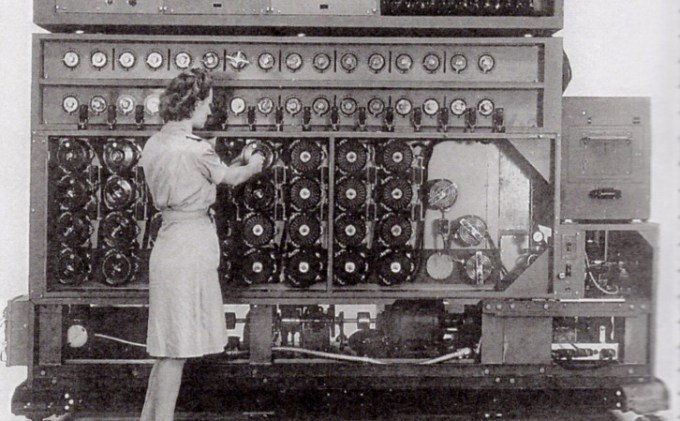

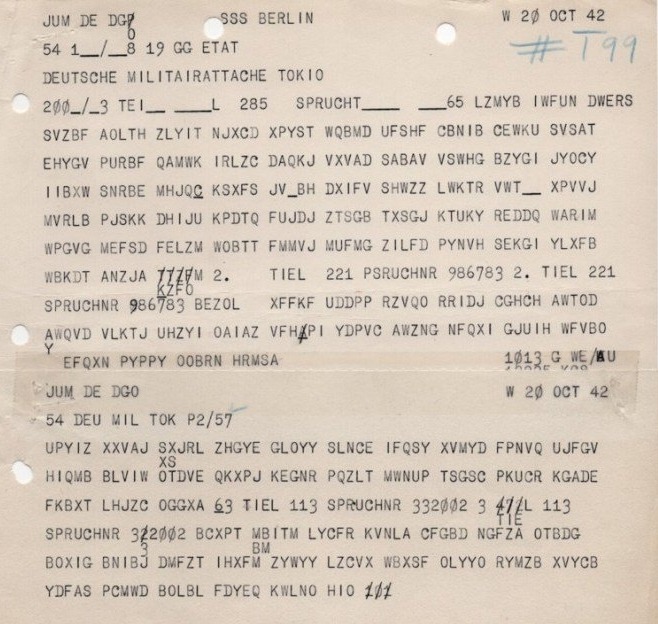

Women operated the machines that tackled the German Enigma ciphers Alan Turing would eventually crack.

These young women’s acumen, and their willingness to accept the cryptic

invitations, would become America’s secret weapon in assembling a

formidable wartime codebreaking operation in record time. They would

also furnish a different model of genius - one more akin to the relational genius that makes a forest successful. Mundy writes:

Code breaking is far from a solitary endeavor, and in many ways it’s the opposite of genius. Or, rather: Genius itself is often a collective phenomenon. Success in code breaking depends on flashes of inspiration, yes, but it also depends on the careful maintaining of files, so that a coded message that has just arrived can be compared to a similar message that came in six months ago. Code breaking during World War II was a gigantic team effort. The war’s cryptanalytic achievements were what Frank Raven, a renowned naval code breaker from Yale who supervised a team of women, called “crew jobs.” These units were like giant brains; the people working in them were a living, breathing, shared memory. Codes are broken not by solitary individuals but by groups of people trading pieces of things they have learned and noticed and collected, little glittering bits of numbers and other useful items they have stored up in their heads like magpies, things they remember while looking over one another’s shoulders, pointing out patterns that turn out to be the key that unlocks the code.

The Army’s secret African American unit in Virginia, mostly female and unknown to many of their white colleagues, tabulated records of companies trading with Hitler or Mitsubishi.

But although codebreaking has entered the popular imagination through the portal of war, often depicted with a kind of intellectual glamor that aligns it with spies and superheroes, it spans a far vaster cultural spectrum of uses as a tool of communication and un-communication. Mundy examines its history and essential elements:

Codes have been around for as long as civilization, maybe longer. Virtually as soon as humans developed the ability to speak and write, somebody somewhere felt the desire to say something to somebody else that could not be understood by others. The point of a coded message is to engage in intimate, often urgent communication with another person and to exclude others from reading or listening in. It is a system designed to enable communication and to prevent it.

Both aspects are important. A good code must be simple enough to be readily used by those privy to the system but tough enough that it can’t be easily cracked by those who are not. Julius Caesar developed a cipher in which each letter was replaced by a letter three spaces ahead in the alphabet (A would be changed to D, B to E, and so forth), which met the ease-of-use requirement but did not satisfy the “toughness” standard. Mary, Queen of Scots, used coded missives to communicate with the faction that supported her claim to the English throne, which - unfortunately for her - were read by her cousin Elizabeth and led to her beheading. In medieval Europe, with its shifting alliances and palace intrigues, coded letters were an accepted convention, and so were quiet attempts to slice open diplomatic pouches and read them. Monks used codes, as did Charlemagne, the Inquisitor of Malta, the Vatican (enthusiastically and often), Islamic scholars, clandestine lovers. So did Egyptian rulers and Arab philosophers. The European Renaissance — with its flowering of printing and literature and a coming-together of mathematical and linguistic learning - led to a number of new cryptographic systems. Armchair philosophers amused themselves pursuing the “perfect cipher,” fooling around with clever tables and boxes that provided ways to replace or redistribute the letters in a message, which could be sent as gibberish and reassembled at the other end. Some of these clever tables were not broken for centuries; trying to solve them became a Holmes-and-Moriarty contest among thinkers around the globe.

Even in the context of war, even in the subset of women cryptographers, the history of codebreaking predates WWII. It stretches back to the world’s first Great War, to a strange haven under the auspices of a Mad Hatter character by the name of George Fabyan - an eccentric, habitually disheveled millionaire with little formal education, who built himself an elaborate private Wonderland complete with a working lighthouse, a Japanese garden, a Roman-style bathing pool fed by fresh spring water, a Dutch mill transported piece by piece from Holland, and an enormous rope replica of a spider’s web for recreation. On these strange grounds, Fabyan constructed Riverbank Laboratories - a pseudo-scientific shrine to his determination to “wrest the secrets of nature” by way of acoustics, agriculture, and, crucially, literary manuscripts.

Fabyan subscribed to a conspiracy theory that the works of William Shakespeare were actually authored by Sir Francis Bacon, who allegedly encoded evidence of his authorship into the texts. The millionaire acquired rare manuscripts, including a 1623 folio of one of Shakespeare’s plays, then hired a team of researchers — he could afford the best minds in the country - to prove the theory by analyzing the text in search of coded messages. Under these improbable circumstances, he incubated the talent that would become the U.S. military’s first concerted cryptanalytic force.

Among Fabyan’s hires was Elizebeth Smith - an intelligent and driven young midwesterner, one of nine children, who had put herself through college after her father denied her the opportunity. In 1916, Fabyan recruited Smith to be the public face of his Baconian codebreaking operation. Soon after she moved to Riverbank Laboratories, Smith began to suspect that the Shakespearian conspiracy theory was just that, sustained by a cultish team of cranks who fed on confirmation bias as they searched for “evidence.” Among Fabyan’s staff was another doubter - William Friedman, a polymathish geneticist from Cornell, living on the second floor of the windmill. Elizebeth and William bonded over their dissent on long bike rides and swims in the Roman pool. Within a year, they were married - a marriage of equals in every way. But although they saw clearly the ludicrousness of Fabyan’s theory, they were too fascinated by the pure art-science of codes and ciphers to leave. Elizebeth moved into the windmill. The couple would soon become the country’s most sought-after codebreaking team as the government outsourced its cryptanalytic efforts to Riverbank. But although the Friedmans worked in tandem, when the Army set out to hire them, they offered William $3,000 and Elizebeth $1,520.

When the team began working for the government in Washington - both still in their twenties, heading a team of thirty - they were decoding every kind of intercepted foreign communication suspected to contain military information. Some did. Most did not - one turned out to be a Czechoslovakian love letter.

Elizebeth Friedman - who went on to have a formidable career in law

enforcement, training men for a new codebreaking unit for the Coast

Guard - is one of the many women whose stories, all different and all

fascinating, Mundy tells in Code Girls, a thoroughly wonderful read in its entirety. Complement it with the story of the the unheralded women astronomers who revolutionized our understanding of the universe decades before they could vote. 💻📖 📕📔📙📚 📗📘 📒📓📕📗📙📚 📖👀

📜 📝📑 📃 📄 📁📂👀

No comments:

Post a Comment