Remembering one passionate Entomologist

by Lauren Young April 24, 2023

“Numbers are kind of an unnatural thing,” he said. “I can’t even remember the numbers. I have to look at my notebook and see how I evaluated it, whereas the descriptions are much more graphic. I think they’re just a much better way of communicating and conveying the essence of what the numbers are really trying to tell you.”

Schmidt’s unique way of bringing science to a wider public will be long remembered.

He began collecting data for the pain index in 1973 after digging up sandy colonies of harvester ants in Georgia with a research colleague, Debbie, who would eventually become his wife. They were both stung, and Debbie described the episode as a “deep ripping and tearing pain, as if someone were reaching below the skin and ripping muscles and tendons; except the ripping continued with each crescendo of pain.”

“I realized [the harvester ant stings] were dramatically different from honey bees, wasps, and hornets. They are like day and night different,” said Schmidt.

He began to study the medical implications and biochemistry of the venom—the toxic compounds causing stings to often be much more painful than insect bites. Schmidt found that there was a difference in chemistry when the pain and skin reaction varied after a sting and set out to obtain a larger survey.

Collecting data on stings became Schmidt’s side project. While most people would flee, Schmidt went out of his way to get to stinging insects. He’d climbed up a tree to collect an entire nest of black Parachartergus fraternus wasps and convinced a bus filled with scientists to pull over to a bull ant colony in South Australia. He self-assessed the sting of any Hymenoptera he came across when out in the field conducting larger studies on velvet ants or sweat bees. To bring live specimens back to the lab to study their venom, he often used his bare hands to grab fistfuls of the insect and stuffs them into vials. If he didn’t get stung during that process, he’d apply one to his arm to be stung once or twice. He didn’t carry a first aid kit or ointments to prepare for a sting, only lugging ice in a chest to keep the specimens alive and a cellphone in case there was a dire emergency.

“I don’t put on suits of armor or get myself all psyched,” he said. “When I go to the doctor’s office, if I know I’m going to get an injection, it hurts a whole lot more the more I know I’m going to get a big, fat needle stuck in me. It’s very much the same way with stinging insects.”

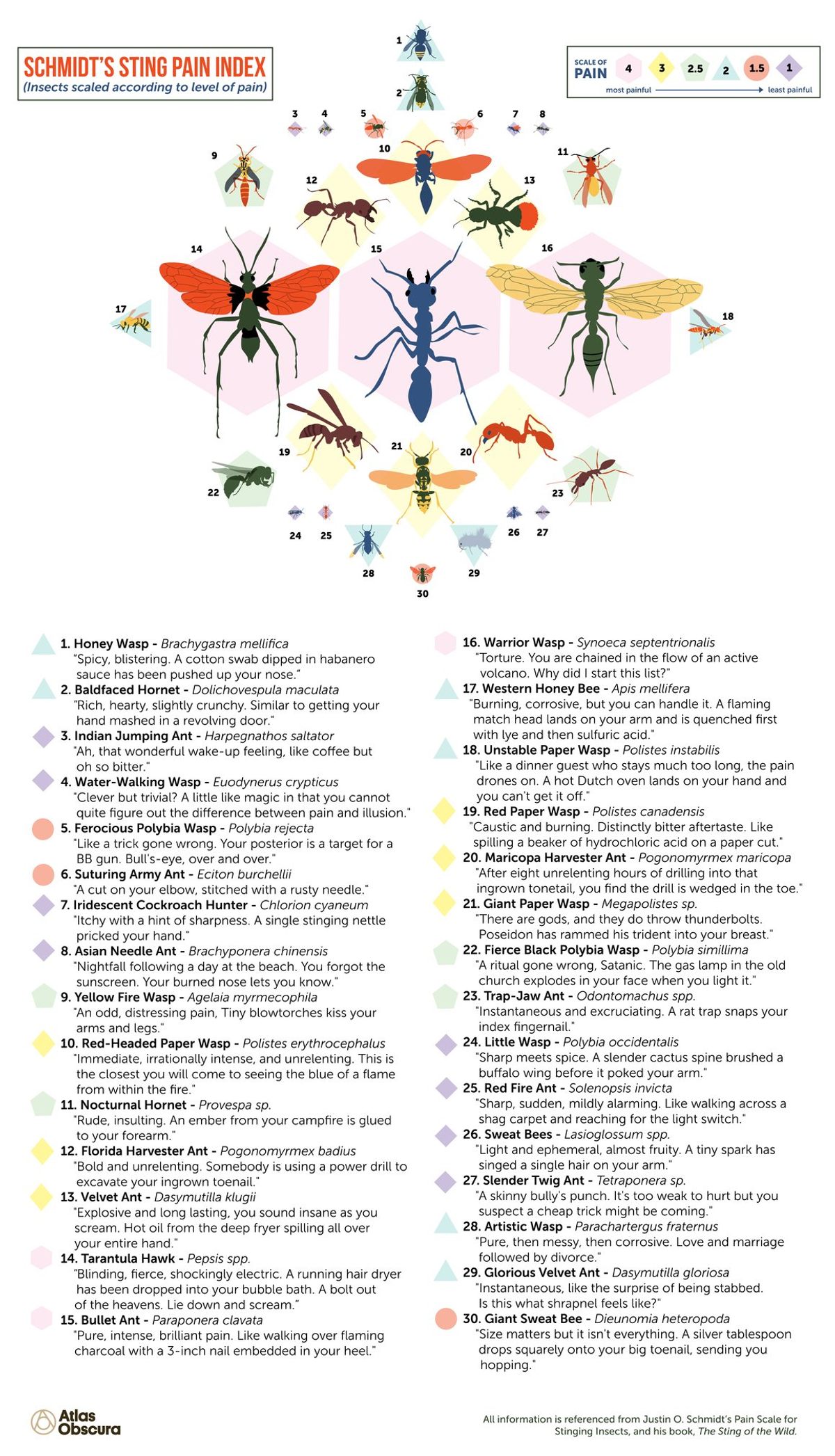

He determined the stinging score by two components: the actual physiological harm and what he called the “ouch factor.” While a universal definition of pain does not exist, Schmidt believed that everyone recognizes that pain comes in a variety of flavors. “Pain truth comes in two flavors, imagined and realized. With stings, our imagination is vivid and strong, even if the sting pain is not realized,” Schmidt explained in the book. He advised that if you are stung by an insect that he rates a four, that you should stop what you’re doing and seek medical aid. “They just shut you down. You can’t function in a normal fashion.”

Schmidt had lost the fear that would surface when he encountered a notoriously nasty stinging insect, but he was not numb to the pain. He once worked on a hive of honey bees and was dressed for the over 100–degree weather in Arizona: a tee shirt and shorts under his bee suit. The honey bees pierced through his thin layer of protection, leaving him with many painfully aching stings. His scores are also similar to the pain evaluations of the few other entomologists who also document sting pain, he said.

What made the Schmidt Pain Index unique was always his elaborate retellings of the stings.

“These descriptions pretty much just hit me,” said Schmidt, who admitted that he was never an “A” student in English. When he sat down to write a sting description, he’d clear his head and think of memories that reminded him of the sting—associating a strike of lighting to the sting of a tarantula hawk and the pain of a messy divorce with the sting of an artistic wasp. He started off describing a few of the stings in this colloquial manner, but realized that it was an effective way to inform people about how much each sting hurt. While the numerical scale is still valuable to entomologists, most people don’t identify with numbers, he explained.

“Numbers are kind of an unnatural thing,” he said. “I can’t even remember the numbers. I have to look at my notebook and see how I evaluated it, whereas the descriptions are much more graphic. I think they’re just a much better way of communicating and conveying the essence of what the numbers are really trying to tell you.”

Schmidt’s unique way of bringing science to a wider public will be long remembered.

How a Lone Researcher Faced Down Millions of Army Ants on the March in Ecuador

Renowned entomologist Frank Nischk remembers when the determined insects tried to invade a field station. - Frank Nischk

*

Podcast: Fairy Circles - An enchanting natural phenomenon in a daunting place.

*

Hawai'i Tackles Invasive Little Fire Ants With Vigilance, Slingshots, and Gooey 'Sputter' Across the archipelago, scientists and citizens are uniting against the tiny terrors, deploying an arsenal of creative weapons. - Ashley Stimpson

*

How a High School Teacher Changed Early 20th-Century Insect Science. Systemic racism kept him from a position in higher education—but it didn't stop Charles Henry Turner from rewriting our understanding of bees, ants, and cockroaches. - Edward D. Melillo

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment