🤴 Le Petit Prince 🤴🏻

The novella is both the most-read and most-translated book

in the French language, and was voted the best book of the 20th century in France.

Translated into more than 250 languages and dialects (as well as braille), selling nearly two million copies annually with sales totalling over 140

million copies worldwide, it has become one of the best-selling books ever

published.

After the outbreak of the Second

World War Saint-Exupéry became exiled in North America.

In the midst of personal upheavals and failing health, he produced almost half

of the writings for which he would be remembered, including a tender tale of

loneliness, friendship, love and loss, in the form of a young prince fallen to

Earth. An earlier memoir by the author had recounted his aviation experiences

in the Sahara Desert,

and he is thought to have drawn on those same experiences in The Little

Prince.

Overview

The Little Prince is a poetic tale, with watercolor

illustrations by the author, in which a pilot stranded in the desert meets a

young prince fallen to Earth from a tiny asteroid. The

story is philosophical and includes social criticism, remarking on the

strangeness of the adult world. It was written during a period when Saint-Exupéry fled to North America

subsequent to the Fall of France during the Second

World War, witnessed first hand by the author and captured in his memoir Flight

to Arras. The adult fable, according to one review, is actually "...an allegory of

Saint-Exupéry's own life - his search for childhood certainties and interior

peace, his mysticism, his belief in human courage and brotherhood.... but also

an allusion to the tortured nature of their relationship."

Though ostensibly styled as a children's book, The Little Prince

makes several observations about life and human nature.

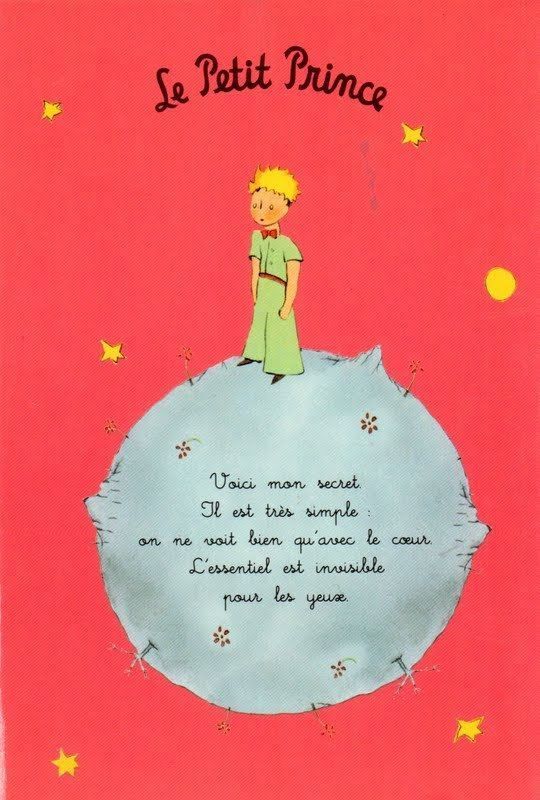

For example, Saint-Exupéry tells

of a fox meeting the

young prince during his travels on Earth. The story's essence is contained in

the lines uttered by the fox to the little prince: On ne voit bien qu'avec

le cœur.

L'essentiel est invisible pour les yeux.

"One sees clearly

only with the heart.

What is essential is invisible to the eye."

Other key thematic messages are

articulated by the fox, such as: Tu deviens responsable pour toujours de ce

que tu as apprivoisé. ("You become responsible, forever, for what you

have tamed.") and C'est le temps que tu as perdu pour ta rose qui fait

ta rose si importante. ("It is the time you have lost for your rose

that makes your rose so important.") The fox's messages are arguably the

book's most famous quotations because they deal with human relationships.

Plot

The narrator explains that, as a young boy, he once drew a

picture of a boa constrictor with an elephant

digesting in its stomach; however, every adult who saw the picture would

mistakenly interpret it as a drawing of a hat. Whenever the narrator would try

to correct this confusion, he was ultimately advised to set aside drawing and

take up a more practical or mature hobby. The narrator laments the lack of

creative understanding displayed by adults.

Now an adult himself, the narrator has become a pilot, and,

one day, his plane crashes in the Sahara desert, far from civilization. Here, the narrator is

suddenly greeted by a young boy or small man whom he refers to as "the little

prince". The little prince asks the narrator to draw a sheep. The narrator

first shows him his old picture of the elephant inside the snake, which, to the

narrator's surprise, the prince interprets correctly. After a few failed

attempts at drawing a good-looking sheep, the narrator simply draws a box in

his frustration, claiming that the box holds a sheep inside. Again, to the

narrator's surprise, the prince exclaims that this is exactly the picture he

wanted. The narrator says that the prince has a strange habit of avoiding

directly answering any of the narrator's questions. The prince is described as

having golden hair, a scarf, and a lovable laugh.

Over the course of eight days stranded in the desert, as the

narrator attempts to repair his plane, the little prince recounts the story of

his life. The prince begins by describing life on his tiny home planet: in

effect, an asteroid

the size of a house (which the narrator believes to be the one known as B-612).

The asteroid's most prominent features are three minuscule volcanoes (two

active, and one dormant or extinct) as well as a variety of plants. The

prince describes spending his earlier days cleaning the volcanoes and weeding

out certain unwanted seeds and sprigs that infest his planet's soil; in

particular, pulling out baobab trees that are constantly trying to grow and overrun

the surface. The prince appears to want a sheep to eat such undesirable plants,

until the narrator informs him that a sheep will even eat roses with thorns.

Upon hearing this, the prince tells of his love for a mysterious rose that

suddenly began growing on the asteroid's surface some time ago. The prince says

he nourished the rose and listened to her when she told him to make a screen or

glass globe to protect her from the cold wind. Although the prince fell in love

with the rose, he also began to feel that she was taking advantage of him, and

he resolved to leave the planet to explore the rest of the universe. Although

the rose finally apologized for her vanity, and the two

reconciled, she encouraged him to go ahead with his journey and so he traveled

onward.

The prince has since visited six other asteroids, each of

which was inhabited by a foolish, narrow-minded adult, including: a king with

no subjects; a conceited man, who believed himself the most admirable person on

his otherwise uninhabited planet; a drunkard who drank to forget the shame of

being a drunkard; a businessman who endlessly counted the stars and absurdly

claimed to own them all; a lamplighter who mindlessly extinguished and

relighted a lamp every single minute; and an elderly geographer,

so wrapped up in theory that he never actually explored the world that he

claimed to be mapping. When the geographer asked the prince to describe his

home, the prince mentioned the rose, and the geographer explained that he does

not record "ephemeral" things, such as roses. The prince was

shocked and hurt by this revelation, since the rose was of great importance to

him on a personal level. The geographer recommended that the prince next visit

the planet

On Earth, the prince landed in the desert, leading him to

believe that Earth was uninhabited. He then met a yellow snake that claimed to

have the power to return him to his home, if he ever wished to return. The

prince next met a desert flower, who told him that she had only seen a handful

of men in this part of the world and that they had no roots, letting the wind

blow them around and living hard lives. After climbing the highest mountain he

had ever seen, the prince hoped to see the whole of Earth, thus finding the

people; however, he saw only the enormous, desolate landscape. When the prince

called out, his echo answered him, which he interpreted as the mocking voices

of others. Eventually, the prince encountered a whole row of rosebushes,

becoming downcast at having once thought that his own rose was unique. He began

to feel that he was not a great prince at all, as his planet contained only

three tiny volcanoes and a flower that he now thought of as common. He lay down

in the grass and wept, until a fox came along. The fox desired to be tamed and

explained to the prince that his rose really was indeed unique and special, because

she was the object of the prince's love. The fox also explained that, in a way,

the prince had tamed the rose, and that this is why the prince was now feeling

so responsible for her. The prince then took time to tame the fox, though the

two ultimately parted ways, teary-eyed. The prince next came across a railway

switchman, who told him how passengers constantly rushed from one place to

another aboard trains, never satisfied with where they were and not knowing

what they were after; only the children among them ever bothered to look out

the windows. A merchant then talked to the prince about his product, a pill

that eliminated thirst, which was very popular, saving people fifty-three

minutes a week. The prince replied that he would instead gladly use that extra

time to go around finding fresh water.

Back in the present moment, it is the eighth day after the

narrator's plane-crash and the narrator is dying of thirst; fortunately, he and

the prince together find a well. The narrator later finds the prince talking to

the snake, discussing his return home and eager to see his rose again, who he

worries has been left to fend for herself. The prince bids an emotional

farewell to the narrator and states that if it looks as though he has died, it

is only because his body was too heavy to take with him to his planet. The

prince warns the narrator not to watch him leave, as it will make him upset.

The narrator, realizing what will happen, refuses to leave the prince's side;

the prince consoles the narrator by saying that he only need look at the stars

to think of the prince's lovable laughter, and that it will seem as if all the

stars are laughing. The prince then walks away from the narrator and allows the

snake to bite him, falling without making a sound.

The next morning, the narrator tries to look for the prince,

but is unable to find his body. The story ends with the narrator's drawing of

the landscape where the prince and the narrator met and where the snake took

the prince's life. The narrator requests that anyone in that area encountering

a small man who refuses to answer questions should contact the narrator

immediately.

Tone and writing style

The story of The Little Prince is recalled in a

sombre, measured tone by the pilot-narrator, in memory of his small friend,

"a memorial to the prince—not just to the prince, but also to the time the

prince and the narrator had together".

The Little Prince was

created when Saint-Exupéry was "...an expatriate

and distraught about what was going on in his country and in the world."

It was written during his 27 month sojourn in North

America, almost as a sort of credo,

"carefully employing the expressions of despair, loneliness, and triumph

throughout its plot-line."

According to one analysis, "the story of the Little

Prince features a lot of fantastical, unrealistic elements... You can't ride a

flock of birds to another planet... The fantasy of the Little Prince works

because the logic of the story is based on the imagination of children, rather

than the strict realism of adults."

An exquisite literary perfectionist akin to the 19th century

French poet Stéphane Mallarmé,

Saint-Exupéry produced draft pages

"covered with fine lines of handwriting, much of it painstakingly crossed

out, with one word left standing where there were a hundred words, one sentence

substitut[ing] for a page...."

He worked "long hours with

great concentration". According to the author himself it was extremely

difficult to start his creative writing processes.

Biographer Paul Webster wrote of

the aviator-author's style "Behind Saint-Exupéry's quest for perfection

was a laborious process of editing and rewriting which reduced original drafts

by as much as two-thirds of their length."

The French author frequently wrote

at night, usually starting about 11 p.m. accompanied by a tray of strong black

coffee. In 1942 Saint-Exupéry related to his American English teacher, Adèle

Breaux, that at such a time of night he felt "free" and able to

concentrate, "writing for hours without feeling tired or sleepy"

until he instantaneously dozed off.

He would wake up later, in

daylight, still at his desk with his head on his arms. Saint-Exupéry stated it

was the only way he could work, as once he started a writing project it became

an obsession. Though the story is more or less understandable, the narrator made

almost no connection from when the little prince travelled between

planets. He purposely did that so that the book felt like it was told

from a secretive little boy.

Although Saint-Exupéry was a master of the French language, he

was never able to achieve anything more than haltingly poor English.

Adèle Breaux, his young Northport

English tutor to whom he later dedicated a writing ("For Miss Adèle

Breaux, who so gently guided me in the mysteries of the English

language") related her experiences with her famous student as Saint-Exupéry in America, 1942–1943: A Memoir, published in 1971.

"Saint-Exupéry's prodigious writings and studies of literature

sometimes gripped him, and on occasion he continued his readings of

literary works until moments before take-off on solitary military

reconnaissance flights, as he was adept at both reading and writing

while flying. Taking off with an open book balanced on his leg, his ground crew

would fear his mission would quickly end after contacting something

'very hard'. On one flight, to the chagrin of colleagues awaiting his

arrival, he circled the Tunis airport for an hour so that he could

finish reading a novel. Saint-Exupéry frequently flew with a lined carnet

(notebook) during his long, solo flights, and some of his philosophical

writings were created during such periods when he could reflect on the

world below him, becoming 'enmeshed in a search for ideals which he

translated into fable and parable'."

Inspirations

Events and characters

Saint-Exupéry next to his crashed Simoun (lacking an

all-critical radio) after impacting the Sahara Desert about

3 am during an air race to Saigon,

Vietnam. His

survival ordeal was about to begin (Egypt, 1935).

On December 30, 1935, at 02:45 am, after 19 hours and

44 minutes in the air, Saint-Exupéry, along with his copilot-navigator André

Prévot, crashed in the Sahara desert.

They were attempting to break the

speed record for a Paris-to-Saigon

flight in a then-popular type of air race, called a raid, and win a

prize of 150,000 francs.

Their plane was a Caudron C-630

Simoun, and the crash site is thought to have been

near to the Wadi Natrun valley, close to the Nile Delta.

Both miraculously survived the crash, only to face rapid

dehydration in the intense desert heat. Their maps were primitive and

ambiguous. Lost among the sand dunes with a few grapes, a thermos of coffee, a

single orange, and some wine, the pair had only one day's worth of liquid. They

both began to see mirages,

which were quickly followed by more vivid hallucinations.

By the second and third days, they were so dehydrated that they stopped

sweating altogether. Finally, on the fourth day, a Bedouin on a

camel discovered them and administered a native rehydration treatment that

saved Saint-Exupéry and Prévot's lives.

The prince's home, "Asteroid B-612", was likely

derived as a progression of one of the planes Saint-Exupéry flew as an airmail pilot, which

bore the serial number "A-612". During his service as a mail pilot in

the North African Sahara desert, Saint-Exupéry had viewed a fennec

(desert sand fox), which most likely inspired him to create the fox character

in the book. In a letter written to his sister Didi from the Western Sahara's Cape Juby,

where he was the manager of an airmail stopover station in 1928, he tells of

raising a fennec which he adored.

In the novella the Wise Fox, believed to be modelled after

the author's intimate New York City

friend Silvia Hamilton Reinhardt, tells the prince that his rose is unique and

special, because she is the one that he loves.

The novella's iconic phrase,

"One sees clearly only with the heart", is believed to have been

suggested by Silvia Hamilton.

The fearsome, grasping baobab trees,

researchers have contended, were meant to represent Nazism attempting

to destroy the planet.

The little prince's reassurance to

the pilot that his dying body is only an empty shell resembles the last words

of Antoine's dying younger brother François, who told the author, from his

deathbed: "Don't worry. I'm all right. I can't help it. It's my

body".

The literary device of presenting philosophical and social

commentaries in the form of the impressions gained by a fictional

extraterrestrial visitor to Earth had already been used by the philosopher and

satirist Voltaire

in his story Micromégas of 1752 — a classic work of French

literature with which Saint-Exupéry was likely familiar.

The Rose 🌹

The Rose in The Little Prince was likely inspired by

Saint-Exupéry's Salvadoran wife, Consuelo (Montreal, 1942).

Many researchers believe that the prince's petulant, vain

rose was inspired by Saint-Exupéry's Salvadoran

wife Consuelo,

with the small home planet being inspired by her small home country El Salvador,

also known as "The Land of Volcanoes".

Despite a raucous marriage,

Saint-Exupéry kept Consuelo close to his heart and portrayed her as the

prince's Rose whom he tenderly protects with a wind screen and under a glass

dome on his tiny planet. Saint-Exupéry's infidelity and the doubts of his

marriage are symbolized by the vast field of roses the prince encounters during

his visit to Earth.

This view of Consuelo was described by biographer Paul

Webster who stated she was "the muse to whom Saint-Exupéry poured out his

soul in copious letters... Consuelo was the rose in The Little Prince.

"I should have judged her by her acts and not by her words," says the

prince. "She wrapped herself around me and enlightened me. I should never

have fled. I should have guessed at the tenderness behind her poor ruses."

The Prince 🤴

Saint-Exupéry may have drawn inspiration

for the prince's character and appearance from his own self as a youth, as

during his early years friends and family called him le Roi-Soleil (the

Sun King) due to his golden curly hair. The author had also met a precocious

eight-year-old with curly blond hair while residing with a family in Quebec City, Canada in 1942, Thomas De Koninck, the son of philosopher Charles De Koninck. Another possible inspiration for the little

prince has been suggested as Land Morrow Lindbergh, the young, golden-haired

son of the pioneering American aviator Charles

Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow all of whom met him during an

overnight stay at their Long Island home in 1939.

Some have seen the prince as a Christ figure, as the child

is sin-free and "believes in a life after death", subsequently

returning to his personal heaven.

Life

photojournalist John Phillips provided a direct answer

to the question of the character's origin when he questioned the author-aviator

on his inspiration for the child character. After Phillips posed the question,

Saint-Exupéry replied that "...one day he looked down on what he thought

was a blank sheet and saw a small childlike figure." When Phillips asked

who the figure was, the author replied "I'm the Little Prince".

One of Saint-Exupéry's earliest literary references to a

small prince is to be found in his second news dispatch from Moscow, dated May

14, 1935. In his writings as a special correspondent for Paris-Soir

the author described his transit from France to the U.S.S.R. by train.

Late at night during the train trip he ventured from his first class

accommodation into the third class carriages, where he came upon large groups

of Polish families huddled together, returning to their homeland. His

commentary not only described a diminutive prince, but also touched on several other

themes Saint-Exupéry incorporated into various philosophical writings: I sat down [facing a sleeping] couple. Between the man and the woman a child had hollowed himself out a place and fallen asleep. He turned in his slumber, and in the dim lamplight I saw his face. What an adorable face! A golden fruit had been born of these two peasants..... This is a musician's face, I told myself. This is the child Mozart. This is a life full of beautiful promise. Little princes in legends are not different from this. Protected, sheltered, cultivated, what could not this child become? When by mutation a new rose is born in a garden, all gardeners rejoice. They isolate the rose, tend it, foster it. But there is no gardener for men. This little Mozart will be shaped like the rest by the common stamping machine.... This little Mozart is condemned.

—A Sense of Life: En Route to the U.S.S.R.

Background

The writer-aviator on Lac

Saint-Louis during a speaking tour in support of France after its armistice with Germany.

He started his work on the novella shortly after returning to the United States (Quebec,1942).

Upon the outbreak of the Second

World War, Saint-Exupéry, a laureate of several of

France's highest literary awards and a successful pioneering aviator prior to

the war, initially flew with a reconnaissance squadron as a reserve military

pilot in the Armée de l'Air (French Air Force).

After France's defeat in

1940 and its armistice with Germany, he

and his wife Consuelo fled occupied France and sojourned in North

America, with Saint-Exupéry first arriving by himself at the very

end of December 1940. His intention for the visit was to convince the United States

to quickly enter the war against Nazi

Germany and the Axis forces, and he soon became one of the expatriate

voices of the French Resistance. In the midst of personal

upheavals and failing health he produced almost half of the writings he would

be remembered for, including a tender tale of loneliness, friendship, love and

loss, in the form of a young prince fallen to Earth.

An earlier memoir by the author

recounted his aviation experiences in the Sahara and he is

thought to have drawn on those same experiences for use as plot elements in The

Little Prince.

Saint-Exupéry wrote and illustrated the manuscript during

the summer and fall of 1942. Although greeted warmly by French-speaking

Americans and by fellow expatriates who had preceded him to New York, his 27 month stay would be marred

by health problems and racked with periods of severe stress, martial and

marital strife. These included partisan attacks on the author's neutral stance

towards ardent French

Gaullist and collaborationist Vichy supporters. According to Saint-Exupéry's American

translator (the author was unable to become proficient in English), "[h]e

was restless and unhappy in exile, seeing no way to fight again for his country

and refusing to take part in the political quarrels that set Frenchman against

Frenchman".

However the period was to be both

a "dark but productive time" during which he created three important

works.

Between January 1941 and April 1943 the Saint-Exupérys lived

in two penthouse apartments on Central Park South,

then the Bevin House mansion in Asharoken, Long Island, N.Y., and still later

at a rented house on Beekman Place in New York City. The couple also stayed in Quebec, Canada, for five

weeks during the late spring of 1942, where they met a precocious

eight-year-old boy with blond curly hair, Thomas, the son of philosopher Charles De Koninck with whom the Saint-Exupéry's

resided. During an earlier

visit to Long Island in August 1939,

Saint-Exupéry had also met Land Morrow Lindbergh, the young, golden-haired son

of the pioneering American aviator Charles

Lindbergh and his wife Anne Morrow.

After returning to the United

States from his Quebec

speaking tour, Saint-Exupéry was pressed to work on a children's book by

Elizabeth Reynal, one of the wives of his U.S. publisher, Reynal & Hitchcock. The French wife of

Eugene Reynal had closely observed Saint-Exupéry for several months, and noting

his ill health and high stress levels, suggested to him that working on a

children's story would help. The author wrote and illustrated The Little

Prince at various locations in New York City,

but principally in the Long Island north-shore

community of Asharoken in mid-to-late 1942, with the

manuscript being completed in October.

Although the book was started in his Central Park South penthouse, Saint-Exupéry

soon found New York City's

noise and sweltering summer heat too uncomfortable to work in, so Consuelo was

dispatched to find improved accommodations. After spending some time at an

unsuitable clapboard country house in Westport, Connecticut,

the newer result was to be the Bevin House,

a 22 room mansion in Asharoken overlooking Long

Island Sound. The author-aviator initially complained, "I wanted a hut

[but it's] the Palace of Versailles"; but as the weeks

wore on and the author became invested in his project, the home would become

"....a haven for writing, the best place I have ever had anywhere in my

life". He devoted himself to the book on mostly midnight shifts,

usually starting at about 11 p.m.,

fueled by helpings of scrambled eggs on English muffins, gin and tonics,

Coca-Colas, cigarettes and numerous reviews by friends and expatriates who

dropped in to see their famous countryman. Included among the reviewers was

Consuelo's Swiss writer paramour Denis de Rougemont, who also modeled for a

painting of the Little Prince lying on his stomach, feet and arms extended up

in the air. De Rougemont

would later help Consuelo write her autobiography, The Tale of the Rose,

as well as write his own biography of Saint-Exupéry.

While the author's personal life was frequently chaotic, his

creative process while writing was disciplined. Christine Nelson, curator of

literary and historical manuscripts at the Morgan Library and Museum which had

obtained Saint-Exupéry's original manuscript in 1968 stated: "On the one

hand, he had a clear vision for the shape, tone, and message of the story. On

the other hand, he was ruthless about chopping out entire passages that just

weren't quite right", eventually distilling the 30,000 word manuscript,

accompanied by small illustrations and sketches, to approximately half its

original length.

The story, the curator added, was created when he was "...an ex-patriot

and distraught about what was going on in his country and in the world."

The large white Second French Empire style mansion, hidden

behind tall trees, afforded the writer a multitude of work environments

although he usually wrote at a large dining table.

It also allowed him to alternately work on his writings, and then on his

sketches and watercolours for hours at a time, moving his armchair and paint

easel from the library towards the parlor one room at a time in order to follow

the sun's light. His meditative view of the sunsets at the Bevin House

eventually became part of the gist of The Little Prince, in which 43

daily sunsets would be discussed. "On your planet..." the story told,

"...all you need do is move your chair a few steps."

Manuscript

The original 140-page autograph

manuscript of The Little Prince, along with various drafts and trial

drawings, were acquired from the author's close friend Silvia Hamilton in 1968

by curator Herbert Cahoon of the Pierpont Morgan Library (now The Morgan Library & Museum) in

Manhattan,

New York City.

It is the only known surviving handwritten draft of the complete work.

The manuscript's pages include large amounts of the author's prose that was struck-through

and therefore not published as part of the first edition. In addition to the

manuscript, several watercolour illustrations by the author are

also held by the museum. They were not part of the first edition. The

institution has marked both the 50th and 70th anniversaries of the novella's

publication, along with the a centenary celebration of the author's birth, with

major exhibitions of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's literary works.

Physically, the manuscript's onion skin media has become brittle and subject to damage.

Saint-Exupéry's handwriting is described as being doctor-like, verging on

indecipherable.

The story's keynote aphorism, On

ne voit bien qu'avec le cœur. L'essentiel est invisible pour les yeux

("One sees clearly only with the heart. What is essential is invisible to

the eye") was reworded and rewritten some 15 times before achieving its

final phrasing. Saint-Exupéry also used his newly purchased $700 Dictaphone

recorder to produce oral drafts for his typist.

His initial 30,000 word working manuscript was distilled to less than half its

original size through laborious editing sessions. Multiple versions of its many

pages were created and its prose then polished over several drafts, with the

author occasionally telephoning friends at 2:00 a.m. to solicit opinions

on his newly written passages.

Many pages and illustrations were cut from the finished work

as he sought to maintain a sense of ambiguity to the story's theme and

messages. Included among the deletions in its 17th chapter were references to

locales in New York, such as the Rockefeller Center and Long Island.

Other deleted pages described the prince's vegetarian diet and the garden on

his home asteroid that included beans, radishes, potatoes and tomatoes, but

which lacked fruit trees that might have overwhelmed the prince's planetoid.

Deleted chapters discussed visits to other asteroids occupied by a retailer

brimming with marketing phrases, and an inventor whose creation could produce

any object desired at a touch of its controls. Likely the result of the ongoing

war in Europe weighing on Saint-Exupéry's shoulders, the author produced a

sombre three page epilogue lamenting "On one star someone has lost a

friend, on another someone is ill, on another someone is at war...", with

the story's pilot-narrator noting of The Prince: "he sees all that. . . .

For him, the night is hopeless. And for me, his friend, the night is also hopeless."

The draft epilogue was also omitted from the novella's printing.

In April 2012 a Parisian auction house announced the

discovery of two previously unknown draft manuscript pages that had been found

and that included new text.

In the newly discovered material the Prince meets his first Earthling after his

arrival. The person he meets is an "ambassador of the human spirit".

The ambassador is too busy to talk, saying he is searching for a missing six

letter word: "I am looking for a six-letter word that starts with G that

means 'gargling'," he says. Saint-Exupéry's text does not say what the

word is, but experts believe it could be "guerre" (or

"war"). The novella thus takes a more politicized tack with an

anti-war sentiment, as 'to gargle' in French is an informal reference to

'honour', which the author may have viewed as a key factor in military

confrontations between nations.

Dedication

Saint-Exupéry met Léon

Werth (1878–1955), a writer and art critic, in 1931. Werth soon became

Saint-Exupery's closest friend outside of his Aeropostale associates. Werth was an anarchist, a

leftist Bolshevik

supporter and of Jewish

descent, twenty-two years older than Saint-Exupéry. Werth was

Saint-Exupéry's very opposite.

Saint-Exupéry dedicated two books to him, Lettre à un otage (Letter to a Hostage)

and Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince), and referred to Werth in

three more of his works. At the beginning of the Second World War while writing

The Little Prince, Saint-Exupéry lived in his downtown New York City apartment, thinking of his

native France and his friends. Werth spent the war unobtrusively in Saint-Amour,

his village in the Jura, a mountainous region near Switzerland

where he was "alone, cold and hungry", a place that had few polite

words for French refugees. Werth appears in the preamble to the novella, where

Saint-Exupéry dedicates the book to him. It reads:

To Leon Werth

I ask children to forgive me for dedicating this book to a grown-up. I have a serious excuse: this grown-up is the best friend I have in the world. I have another excuse: this grown-up can understand everything, even books for children. I have a third excuse: he lives in France where he is hungry and cold. He needs to be comforted. If all these excuses are not enough then I want to dedicate this book to the child whom this grown-up once was. All grown-ups were children first. (But few of them remember it.) So I correct my dedication:

To Leon Werth,

Le Petit Prince est une œuvre de langue française, la plus connue d'Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Publié en 1943 à New York simultanément à sa traduction anglaise, c'est une œuvre poétique et philosophique sous l'apparence d'un conte pour enfants.

Traduit en cinq cent trente-cinq langues et dialectes différents2, Le Petit Prince est l'ouvrage le plus traduit au monde après la Bible3.

Le langage, simple et dépouillé, parce qu'il est destiné à être

compris par des enfants, est en réalité pour le narrateur le véhicule

privilégié d'une conception symbolique

de la vie. Chaque chapitre relate une rencontre du petit prince qui

laisse celui-ci perplexe, par rapport aux comportements absurdes des

« grandes personnes ». Ces différentes rencontres peuvent être lues

comme une allégorie.

Les aquarelles font partie du texte4 et participent à cette pureté du langage : dépouillement et profondeur sont les qualités maîtresses de l'œuvre.

On peut y lire une invitation de l'auteur à retrouver l'enfant en

soi, car « toutes les grandes personnes ont d'abord été des enfants.

(Mais peu d'entre elles s'en souviennent.) ». L'ouvrage est dédié à Léon Werth, mais « quand il était petit garçon ».

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Petit_Prince

*************************

When he was a little boy

Saint-Exupéry's aircraft disappeared over the Mediterranean in July 1944. The following month, Werth learned of his friend's disappearance from a radio broadcast. Without having yet heard of The Little Prince, in November, Werth discovered that Saint-Exupéry had published a fable the previous year in the U.S., which he had illustrated himself, and that it was dedicated to him. At the end of the Second World War, which Antoine de Saint-Exupéry didn't live to see, Werth said: "Peace, without Tonio (Saint-Exupéry) isn't entirely peace." Werth did not see the text for which he was so responsible until five months after his friend's death, when Saint-Exupéry's French publisher, Gallimard, sent him a special edition. Werth died in Paris in 1955.

Illustrations

All of the novella's simple but elegant watercolour illustrations, which were integral to the story, were painted by Saint-Exupéry. He had studied architecture as a young adult but nevertheless could not be considered an artist — which he self-mockingly alluded to in the novella's introduction. Several of his illustrations were painted on the wrong side of the delicate onion skin paper that he used, his medium of choice. As with some of his draft manuscripts, he occasionally gave away preliminary sketches to close friends and colleagues; others were even recovered as crumpled balls from the floors in the cockpits he flew. Two or three original Little Prince drawings were reported in the collections of New York artist, sculptor and experimental filmmaker Joseph Cornell. One rare original Little Prince watercolour would be mysteriously sold at a second-hand book fair in Japan in 1994, and subsequently authenticated in 2007.

An unrepentant lifelong doodler and sketcher, Saint-Exupéry had for many years sketched little people on his napkins, tablecloths, letters

to paramours and friends, lined notebooks and other scraps of paper. Early figures took on a multitude of appearances, engaged in a variety of tasks. Some appeared as doll-like figures, baby puffins, angels with wings, and even a figure similar to that in Robert Crumb's later famous Keep On Truckin' of 1968. In a 1940 letter to a friend he sketched a character with his own thinning hair, sporting a bow tie, viewed as a boyish alter-ego, and he later gave a similar doodle to Elizabeth Reynal at his New York publisher's office. Most often the diminutive figure was expressed as "...a slip of a boy with a turned up nose, lots of hair, long baggy pants that were too short for him and with a long scarf that whipped in the wind. Usually the boy had a puzzled expression... [T]his boy Saint-Exupéry came to think of as "the little prince," and he was usually found standing on top of a tiny planet. Most of the time he was alone, sometimes walking up a path. Sometimes there was a single flower on the planet." His characters were frequently seen chasing butterflies; when asked why they did so, Saint-Exupéry, who thought of the figures as his alter-egos, replied that they were actually pursuing a "realistic ideal". Saint-Exupéry eventually settled on the image of the young, precocious child with curly blond hair, an image which would become the subject of speculations as to its source. One "most striking" illustration depicted the pilot-narrator asleep beside his stranded plane prior to the prince's arrival. Although images of the narrator were created for the story, none survived Saint-Exupéry's editing process.

To mark both the 50th and 70th anniversaries of The Little Prince's publication, the Morgan Library and Museum mounted major exhibitions of Saint-Exupéry's draft manuscript, preparatory drawings, and similar materials that it had obtained earlier from a variety of sources. One major source was an intimate friend of his in New York City, Silvia Hamilton (later, Reinhardt), to whom the author gave his working manuscript just prior to returning to Algiers to resume his work as a Free French Air Force pilot. Hamilton's black poodle,

Mocha, is believed to have been the model for the Little Prince's sheep, with a Raggedy Ann type doll helping as a stand-in for the prince.

Additionally, a pet boxer, Hannibal, that Hamilton gave to him as a gift may have been the model for the story's desert fox and its tiger. A museum representative stated that the novella's final drawings were lost.

Seven unpublished drawings for the book were also displayed at the museum's exhibit, including fearsome looking baobab trees ready to

destroy the prince's home asteroid, as well as a picture of the story's narrator, the forlorn pilot, sleeping next to his aircraft. That image was likely omitted to avoid giving the story a 'literalness' that would distract its readers, according to one of the Morgan Library's staff. According to Christine Nelson, curator of literary and historical manuscripts

at the Morgan, "[t]he image evokes Saint-Exupéry's own experience of awakening in an isolated, mysterious place. You can almost imagine him wandering without much food and water and conjuring up the character of the Little Prince." Another reviewer noted that the author "...chose the best illustrations... to maintain the ethereal tone he wanted his story to exude. Choosing between ambiguity and literal text and illustrations, Saint-Exupéry chose in every case to obfuscate." Not a single drawing of the story's narrator–pilot survived the author's editing process; "...he was very good at excising what was not essential to his story".

In 2001 Japanese researcher Yoshitsugu Kunugiyama surmised that the cover illustration Saint-Exupéry painted for Le Petit Prince deliberately depicted a stellar arrangement created to celebrate the author's own centennial of birth. According to Kunugiyama, the cover art chosen from one of Saint-Exupéry's watercolour illustrations contained the planets Saturn and Jupiter, plus the

star Aldebaran,

arranged as an isosceles triangle, a celestial configuration which occurred in the early 1940s, and which he likely knew would next reoccur in the year 2000. Saint-Exupéry possessed superior mathematical skills and was a master celestial navigator, a vocation he had studied at Salon-de-Provence with the Armée de l'Air (French Air Force).

Post-publication

Stacy Schiff, one of Saint-Exupéry's principal biographers, wrote of him and his most famous work, "rarely have an author and a character been so intimately bound together as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and his Little Prince", and remarking of their dual fates, "...the two remain tangled together, twin innocents who fell from the sky". Another noted that the novella's mystique was "...enhanced by the parallel between author and subject: imperious innocents whose lives consist of equal parts flight and failed love, who fall to earth, are little impressed with what they find here and ultimately disappear without a trace."

Only weeks after his novella was first published in April 1943, despite his wife's pleadings and before Saint-Exupéry had received any of

its royalties (he never would), the author-aviator joined the Free French Forces. He would remain immensely proud of The Little Prince, and almost always kept a personal copy with him which he often read to others during the war.

As part of a 32 ship military convoy he voyaged to North Africa where he rejoined his old squadron to fight with the Allies, resuming his work as a reconnaissance pilot despite the best efforts of his

friends, colleagues and fellow airmen who could not prevent him from flying. He had previously escaped death by the barest of margins a number of times, but was then lost in action during a July 1944 spy

mission from the moonscapes of Corsica to the continent in preparation for the Allied

invasion of occupied France, only three weeks before the Liberation of Paris.

Reception

Many of the book's initial reviewers were flummoxed by the fable's multi-layered story line and its morals, perhaps expecting a significantly more conventional story from one of France's leading writers. Its publisher had anticipated such reactions to a work that fell neither exclusively into a children's or adult's literature classification. The New York Times wrote shortly before its

release "What makes a good children's book?.... ...The Little Prince, which is a fascinating fable for grown-ups [is] of conjectural value for boys and girls of 6, 8 and 10. [It] may very well be a book on the order of Gulliver's Travels, something that exists on two levels"; "Can you clutter up a narrative with paradox and irony and still hold the interest of 8 and 10 year olds?" Notwithstanding the

story's duality, the review added that major portions of the story would probably still "capture the imagination of any child."

Addressing whether it was written for children or adults, Reynal & Hitchcock promoted it ambiguously, saying that as far as they were concerned "it's the new book by Saint-Exupéry", adding to its dustcover "There are few stories which in some way, in some degree, change the world forever for their readers. This is one."

Others were not shy in offering their praise. Austin

Stevens, also of The New York Times, stated that the story

possessed "...large portions of the Saint-Exupéry philosophy and poetic

spirit. In a way it's a sort of credo." P.L.

Travers, author of the Mary Poppins series of children books, wrote in a Herald Tribune review: "...The Little Prince will shine upon children with a sidewise gleam. It will strike them in some place that is not the mind and glow there until the time comes for them to comprehend it."

British journalist Neil Clark, in The American Conservative, much later offered an expansive view of Saint-Exupéry's overall work by commenting that it provides a "…bird's eye view of humanity [and] contains some of the most profound observations on the human condition ever written", and that the author's novella "…doesn't merely express his contempt for selfishness and materialism [but] shows how life should be lived."

The book enjoyed only modest initial success, residing on

the The New York Times Best Seller list for only two weeks, as opposed to his earlier 1939 English translation, Wind, Sand and Stars which remained on the same list for nearly five months. As a cultural icon, the novella regularly draws new readers and reviewers, selling almost two million copies annually and also spawning numerous adaptations. Modern-day references to The Little Prince include one from The New York Times that describes it as "abstract" and fabulistic".

As science fiction

Saint-Exupéry made no attempt at scientific accuracy, and the asteroid on which the Little Prince lives bears little resemblance to an actual asteroid belt. Nevertheless, in retrospect, his book could be considered a pioneering work in depicting humans living on asteroids, a theme which would become a staple of many later works of science fiction (see Asteroids in fiction).

Literary translations and printed editions

Some of the more than 250 translations of The Little Prince, these editions displayed at the National Museum of Ethnology,

Osaka, Japan (2013).

Katherine Woods (1886–1968)

produced the classic English translation of 1943 which was later joined by several other English translations. Her original version contained some errors. Mistranslations aside, one reviewer noted that Wood's almost "poetic" English translation has long been admired by many Little Prince lovers who have spanned generations (it stayed in print until 2001), as her work maintains Saint-Exupéry's story-telling spirit and charm, if not its literal accuracy. As of 2014 at least six additional English translations have been published:

David Wilkinson, (bilingual English-French student edition, ISBN

0-9567215-9-1, 1st ed. 2011)

Each of these translators approaches the essence of the

original with his or her own style and focus.

Le Petit Prince is often used as a beginner's book

for French language students, and several bilingual and

trilingual translations have been published. As of 2014 it has been translated

into more than 250 languages and dialects, including Sardinian, the constructed international language of Esperanto,

and the Congolese language Alur, as well as being printed in braille for visually impaired

readers. It is one of the few modern books to have been translated into Latin, as Regulus

vel Pueri Soli Sapiunt. In 2005, the book was also translated into Toba,

an indigenous language of northern Argentina, as

So Shiyaxauolec Nta'a. It was the first book translated into this

language since the New Testament of the Bible. Anthropologist Florence

Tola, commenting on the suitability of the work for Toban translation, said

there is "nothing strange [when] the Little Prince speaks with a snake or

a fox and travels among the stars, it fits perfectly into the Toba

mythology."

Linguists have compared the many translations and even

editions of the same translation for style, composition, titles, wordings and

genealogy. As an example: as of 2011 there are approximately 47 translated

editions of The Little Prince in Korean, and there are also about 50 different

translated editions in Chinese (produced in both mainland China and Taiwan). Many of them are titled Prince

From a Star, while others carry the book title that is a direct translation

of The Little Prince.

By studying the use of word

phrasings, nouns, mistranslations and other content in newer editions,

linguists can identify the source material for each version: whether it was

derived from the original French typescript, or from its first translation into

English by Katherine Woods, or from a number of adapted sources.

The first edition to be published in France, Saint-Exupéry's

birthplace, would not be printed by his regular publisher in that country, Gallimard, until after the Second

World War,

as the author's blunt views within

his eloquent writings were soon banned by the German's Nazi appeasers in Vichy

France. Prior to France's liberation

new printings of Saint-Exupéry's works were made available only by means of

secret print runs, such as

that of February 1943 when 1,000 copies of an underground version of his best seller

Pilote de guerre, describing the German invasion of France, were

covertly printed in Lyon.

Commemorating the novella's 70th anniversary of publication,

in conjunction with the 2014 Morgan Exhibition, Éditions Gallimard released a complete facsimile

edition of Saint-Exupéry's original handwritten manuscript entitled Le

Manuscrit du Petit Prince d'Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: Facsimilé et

Transcription, edited by Alban Cerisier and Delphine Lacroix. The book in

its final form has also been republished in 70th anniversary editions by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (in English)

and by Gallimard (in French).

Spanish editions

After being translated by Bonifacio del Carril, The Little Prince

was first published in Spanish as El

principito in September 1951 by the Argentine

publisher Emecé Editores. Other Spanish editions have also been created;

in 1956 the Mexican

publisher Diana released its first edition of the book, El pequeño príncipe,

a Spanish translation by José María Francés.

Another edition of the work was

produced in 1964, and four years later, in 1968. Editions were also produced in

Colombia and

Cuba, the latter

translation by Luis Fernández in 1961. Chile had its first

translation in 1981; Peru

in February 1985; Venezuela in 1986, and Uruguay in 1990.

Extension of copyrights in France

Due to Saint-Exupéry's wartime death, his estate received

the civil code designation Mort pour la France (English: Died for

France), which was applied by the French Government in 1948. Amongst the

law's provisions is an increase of 30 years in the duration of copyright;

thus most of Saint-Exupéry's

creative works will not fall out of copyright status in France for an extra 30

years.

Adaptations and sequels

The wide appeal of Saint-Exupéry's novella has led to it

being adapted into numerous forms over the decades. Additionally, the little

prince character himself has been adapted to a number of promotional roles,

including as a symbol of environmental protection, by the Toshiba

Group.

He has also been portrayed as a "virtual ambassador" in a campaign against smoking, employed by the Veolia Energy Services Group,

and his name was used as an episode title in the TV series Lost.

The multi-layered fable, styled as a children's story with

its philosophical elements of irony and paradox directed towards adults,

allowed The Little Prince to be transferred into various other art forms and media,

including: 📀

Vinyl record, cassette

and CD:

as early as 1954 several audio editions in multiple languages were created on

vinyl record, cassette tape and much latter as a CD, with one English version

narrated by Richard Burton.

📻

🎬

Film

and TV:

the story has been created as a movie as early as 1966 in a Soviet-Lithuanian production, with its first English movie version in 1974 produced in the United States featuring Bob Fosse, who choreographed his own dance sequence as The Snake, and Gene Wilder as The Fox. A new 3D animated movie of the story was in production as of 2014.

🎭

Stage: The Little Prince's popular appeal has lent

itself to widespread dramatic adaptations in live stage productions at both the professional and amateur levels. It has become a staple of numerous stage companies, with dozens of productions created.

📚

Graphic novel: a new printed version of the story in

comic book form, by Joann Sfar in 2008, drew widespread notice.

🩰

Opera

and ballet:

several operatic and ballet versions of the novella have been produced as early as the Russian Malen′kiy, first performed in 1978 with a symphony score composed in the 1960s.

Other: a number of musical references, game boards and a video game version of the novella have been released.

In 1997, Jean-Pierre Davidts wrote what could be considered a sequel to The Little Prince, entitled Le petit prince retrouvé

(The Little Prince Returns). In this version, the narrator is a shipwrecked man who encounters the little prince on a lone island; the prince has returned to find help against a tiger who threatens his sheep.

Another sequel titled The Return of the Little Prince was written by former actress Ysatis de Saint-Simone, niece of Consuelo de Saint Exupery.

Honours and legacy

Museums and exhibits

Morgan exhibitions

New York City's Morgan Library & Museum mounted three showings of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's original manuscript, with its first showing in 1994 on the occasion of the story's 50th anniversary of publication, followed by one celebrating the author's centennial of birth in 2000, with its last and largest exhibition in 2014 honouring the novella's 70th anniversary.

The 1994 exhibition displayed the original manuscript, translated by the museum's art historian Ruth Kraemer, as well as a number of the story's watercolours drawn from the Morgan's permanent collection. Also included with the exhibits was a 20-minute video it produced, My Grown-Up Friend, Saint-Exupéry, narrated by actor Macaulay Culkin, along with photos of the author, correspondence to his wife Consuelo, a signed first edition of The Little Prince, and several international editions in other languages.

In January 2014 the museum mounted a third, significantly larger exhibition centered on the novella's creative origins and its history. The major showing of The Little Prince: A New York Story celebrated the story's 70th anniversary. It examined both the novella's New York origins and Saint-Exupéry's creative processes, looking at his story and paintings as they evolved from conceptual germ form into progressively more refined versions, and finally into the book's highly polished first edition. "The exhibition allows us to step back to the moment of creation and witness Saint-Exupéry at work..." wrote the museum's director, William Griswold. It was if visitors were able to look over his shoulder as he worked, according to curator Christine Nelson. Funding for the 2014 exhibition was provided by

several benefactors, including The Florence Gould Foundation, The Caroline Macomber Fund, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Air France

and the New York State Council on the Arts.

The new, more comprehensive exhibits included 35 watercolor paintings and 25 of the work's original 140 handwritten manuscript pages, with his almost illegible handwriting penciled onto 'Fidelity' watermarked onion skin paper. The autograph manuscript pages included struck-through content that was not published in the novella's first edition. As well, some 43 preparatory pencil drawings that evolved into the story's illustrations accompanied the manuscript, many of them dampened by moisture that rippled its onion skin media. One painting depicted the prince floating above Earth wearing a yellow scarf was wrinkled, having been crumpled up and thrown away before being retrieved for preservation. Another drawing loaned from Silvia Hamilton's grandson depicted the diminutive prince observing a sunset on his home asteroid; two other versions of the same drawing were also displayed alongside it allowing visitors to observe the drawings progressive refinement. The initial working manuscript and

sketches, displayed side-by-side with pages from the novella's first edition, allowed viewers to observe the evolution of Saint-Exupéry's work.

Shortly before departing the United States to rejoin his reconnaissance squadron in North Africa in its struggle against Nazi Germany, Saint-Exupéry appeared unexpectedly in military uniform at the door of his intimate friend Silvia Hamilton. He presented his working manuscript and its preliminary drawings in a "rumpled paper bag", placed onto her home's entryway table, offering "I'd like to give you something splendid, but this is all I have". Several of the manuscript pages bore accidental coffee stains and cigarette scorch marks. The Morgan later acquired the 30,000 word manuscript from Hamilton in 1968, with its pages becoming the centrepieces of its exhibitions on Saint-Exupéry's work. The 2014 exhibition also borrowed artifacts and the author's personal letters from the Saint Exupéry-d'Gay Estate, as well as materials from other private collections, libraries and museums in the United States and France. Running concurrent with its 2014 exhibition, the Morgan held a series of lectures, concerts and film showings, including talks by Saint-Exupéry biographer Stacy Schiff, writer Adam Gopnik, and author Peter Sis

on his new work The Pilot and The Little Prince: The Life of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry,

Additional exhibits included photos of Saint-Exupéry by Life

photojournalist John Phillips, other photos of the author's New York area homes, an Orson Welles screenplay of the novella the filmmaker attempted to produce as a movie in collaboration with Walt Disney, as well as one of the few signed copies extant of The Little Prince, gifted to Hamilton's 12 year old son.

A tribute to The Little Prince atop Asteroid B-612, at the Museum of The Little Prince, Hakone, Japan (2007).

Permanent exhibits

In Hakone, Japan there is the Museum of The Little Prince featuring outdoor squares and sculptures such as the B-612 Asteroid, the Lamplighter Square, and a sculpture of the Little Prince. The museum grounds additionally feature a Little Prince Park along with the Consuelo Rose Garden; however the main portion of the museum are its indoor exhibits.

In Gyeonggi-do, South Korea,

there is an imitation French village, Petite France, which has adapted the story elements of The Little Prince into its architecture and monuments. There are several sculptures of the story's characters, and the village also offers overnight housing in some of the French-style homes. Featured are the history of The Little Prince, an art gallery, and a small amphitheatre

situated in the middle of the village for musicians and other performances. The enterprise's director stated that in 2009 the village received a half million visitors.

Special exhibitions

In 1996 the Danish sculptor Jens Galschiøt unveiled an artistic arrangement consisting of seven blocks of

granite asteroids 'floating' in a circle around a 2-metre tall planet Earth. The artistic universe was populated by bronze sculpture figures that the little prince met on his journeys. As in the book, the prince discovers that "the essential is invisible to the eye, and only by the heart can you really see". The work was completed at the start of 1996 and placed in the central square of Fuglebjerg, Denmark, but was later stolen from an exhibition in Billund in 2011.

During 2009 in São Paulo, Brazil, the giant Oca Art Exhibition Centre presented The Little Prince as part of 'The Year of France and The Little Prince'. The displays covered over 10,000 square metres on four floors, examining Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince and their philosophies, as visitors passed through theme areas of the desert, different worlds, stars and the cosmos. The ground floor of the exhibit area was laid out as a huge map of the routes flown by the author and Aeropostale in South America and around the world. Also included was a full-scale replica of his Caudron Simoun, crashed in a simulated Sahara desert.

In 2012 the Catalan architect Jan Baca unvelied a sculpture in Terrassa, Catalonia

showing the Little Prince image along the sentence "It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye"

Numismatics and philatelic

The Little Prince at bottom, and a portrait of his creator

on a French 50-franc banknote (1993).

Before France

adopted the euro as

its currency, Saint-Exupéry and drawings from The Little Prince were on

the 50-franc

banknote; the artwork was by Swiss designer Roger Pfund. Among the anti-counterfeiting measures on the

banknote was micro-printed text from Le Petit Prince, visible with a

strong magnifying glass. Additionally, a 100-franc commemorative coin

was also released in 2000, with Saint-Exupéry's image on its obverse, and that of the Little Prince on its

reverse.In commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the writer's

untimely death, Israel

issued a stamp honoring "Saint-Ex" and The Little Prince in

1994.

Philatelic

tributes have been printed in at least 24 other countries as of 2011.

Astronomy

An asteroid discovered in 1975, 2578 Saint-Exupéry, was also named after the

author of The Little Prince.

Another asteroid discovered in 1993 was named 46610 Bésixdouze, which is French for "B six

twelve". The asteroid's number, 46610, becomes B612 in hexadecimal notation. B-612 was the name of the prince's

home asteroid.

Insignia and awards

Prior to its decommissioning in 2010, the GR I/33 (later renamed as the 1/33 Belfort Squadron), one of the French Air Force squadrons Saint-Exupéry flew with, adopted the image of the Little Prince as part of the squadron and tail insignia of its Dassault Mirage fighter jets. Some of the fastest jets in the world were flown with The Prince gazing over their pilots' shoulders.

The Little Prince Literary Award for Persian

fiction by writers under the age of 15, commemorating the title of Saint-Exupéry's famous work, was created in Iran by the Cheragh-e Motale'eh Literary Foundation. In 2012, some 250 works by young authors were submitted for first stage review according to the society's secretary Maryam Sistani, with the selection of the best three writers from 30 finalists being conducted in Tehran that September.

Schools

L'école Le Petit Prince is the public elementary school in the small community of Genech in northern France, dedicated in 1994 upon the merger of two former schools. With nine classrooms and a library, its building overlooks the village's Place Terre des Hommes, a square also named in tribute to

Saint-Exupéry's 1939 philosophical memoir, Terre des hommes.

A K–6 elementary school on Avro Road

in Maple,Ontario, Canada, was also opened in 1994 as L'école élémentaire catholique Le Petit Prince. Its enrollment expanded from 30 students in its first year to some 325 children by 2014. One of Saint-Exupéry's colorful paintings of the prince is found on its website's welcome page.

See also

Author

|

|

Original title

|

Le Petit Prince (as handwritten)

|

Translator

|

(English editions)

Katherine Woods

T.V.F. Cuffe

Irene Testot-Ferry

Alan Wakeman

Richard

Howard

David Wilkinson

|

Illustrator

|

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

|

Cover artist

|

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

|

Country

|

United

States

(English & French)

France (French)

|

Language

|

English, French and 250+ others

|

Publisher

|

|

Publication date

|

1943 (U.S.:

English & French)

1945 (France:

French)

|

Preceded by

|

|

Followed by

|

|

No comments:

Post a Comment