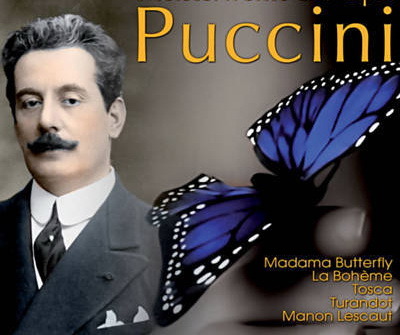

Giacomo Puccini

22 December 1858 ♫ 29 November 1924

Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini was an Italian opera composer who has been called "the greatest composer of Italian opera after Verdi".

Puccini's early work was rooted in traditional late-19th-century

romantic Italian opera. Later, he successfully developed his work in the

realistic verismo style, of which he became one of the leading exponents.

Puccini's most renowned works are La bohème (1896), Tosca (1900), Madama Butterfly (1904), and Turandot (1924), all of which are among the important operas played as standards. .

👇 📺 👇 Opera ♪ Puccini ♫ Click Below to Choose a Video

La Bohème

Puccini's next work after Manon Lescaut was La bohème, a four-act opera based on the 1851 book by Henri Murger, La Vie de Bohème. La bohème premiered in Turin in 1896, conducted by Arturo Toscanini. Within a few years, it had been performed throughout many of the leading opera houses of Europe, including Britain, as well as in the

United States. It was a popular success, and remains one of the most frequently performed operas ever written.

The libretto of the opera, freely adapted from Murger's episodic

novel, combines comic elements of the impoverished life of the young protagonists with the tragic aspects, such as the death of the young seamstress Mimí. Puccini's own life as a young man in Milan served as a source of inspiration for elements of the libretto. During his years as a conservatory student and in the years before Manon Lescaut, he experienced poverty similar to that of the bohemians in La bohème, including chronic shortage of necessities like food, clothing and money

to pay rent. Although Puccini was granted a small monthly stipend by the Congregation of Charity in Rome (Congregazione di caritá), he frequently had to pawn his possessions to cover basic expenses. Early biographers such as Wakeling Dry and Eugenio Checchi, who were

Puccini's contemporaries, drew express parallels between these incidents and particular events in the opera. Checchi cited a diary kept by Puccini while he was still a student, which recorded an occasion in which, as in Act 4 of the opera, a single herring served as a dinner for four people. Puccini himself commented: "I lived that Bohème, when there wasn't yet any thought stirring in my brain of seeking the theme of an opera". ("Quella Bohème io l’ho vissuta, quando ancora non mi mulinava nel cervello l’idea di cercarvi l’argomento per un’opera in musica.")

Puccini's composition of La bohème was the subject of a public dispute between Puccini and fellow composer Ruggiero Leoncavallo. In early 1893, the two composers discovered that they were both engaged in writing operas based on Murger's work. Leoncavallo had started his work first, and he and his music publisher claimed to have "priority" on the subject (althugh Murger's work was in the public domain). Puccini responded that he started his own work without having any knowledge of Leoncavallo's project, and wrote: "Let him compose. I will compose. The audience will decide." Puccini's opera premiered a year before that of Leoncavallo, and has been a perennial audience favorite, while Leoncavallo's version quickly faded into obscurity.

Tosca

Puccini's next work after La bohème was Tosca (1900), arguably Puccini's first foray into verismo, the realistic depiction of many facets of real life including violence. Puccini had been considering an opera on this theme since he saw the

play Tosca by Victorien Sardou in 1889, when he wrote to his publisher, Giulio Ricordi, begging him to get Sardou's permission for the work to be made into an opera: "I see in this Tosca the opera I need, with no overblown proportions, no elaborate spectacle, nor will it call for the usual excessive amount of music."

The music of Tosca employs musical signatures for particular

characters and emotions, which have been compared to Wagnerian leitmotivs, and some contemporaries saw Puccini as thereby adopting a new musical style influenced by Wagner. Others viewed the work differently. Rejecting the allegation that Tosca displayed Wagnerian influences, a critic reporting on the 20 February 1900 Torino

premiere wrote: "I don't think you could find a more Puccinian score than this."

Automobile crash and near death

On 25 February 1903, Puccini was seriously injured in a car crash during a nighttime journey on the road from Lucca to Torre del Lago. The car was driven by Puccini's chauffeur and was carrying Puccini, his future wife Elvira, and their son Antonio. It went off the road, fell several metres, and flipped over. Elvira and Antonio were flung from the car and escaped with minor injuries. Puccini's chauffeur, also thrown from the car, suffered a serious fracture of his femur. Puccini was pinned under the vehicle, with a severe fracture of his right leg and with a portion of the car pressing down on his chest. A doctor living near the scene of the crash, together with another person who came to investigate, saved Puccini from the wreckage. The injury did not heal well, and Puccini remained under treatment for months. During the medical examinations that he underwent it was also found that he was suffering from a form of diabetes. The accident and its consequences slowed Puccini's completion of his next work, Madama Butterfly.

Madama Butterfly

The original version of Madama Butterfly, premiered at La Scala on 17 February 1904 with Rosina Storchio

in the title role. It was initially greeted with great hostility (probably largely owing to inadequate rehearsals). When Storchio's kimono accidentally lifted during the performance, some in the audience started shouting: "The butterfly is pregnant" and "There is the little Toscanini". The latter comment referred to her well publicised affair with Arturo Toscanini. This version was in two acts; after its disastrous premiere, Puccini withdrew the opera, revising it for what was virtually a second premiere at Brescia in May 1904 and performances in Buenos Aires, London, the USA and Paris. In 1907, Puccini made his final revisions to the opera in a fifth version, which has become known as the "standard version". Today, the standard version of the opera is the version most often performed around the world. However, the original 1904 version is occasionally performed as well, and has been recorded.

Later works

La Rondine

Puccini completed the score of La rondine, to a libretto by Giuseppe Adami in 1916 after two years of work, and it was premiered at the Grand Théâtre de Monte Carlo on 27 March 1917. The opera had been originally commissioned by Vienna's Carltheater; however, the outbreak of World War I

prevented the premiere from being given there. Moreover, the firm of Ricordi had declined the score of the opera – Giulio Ricordi's son Tito

was then in charge and he described the opera as "bad Lehár". It was taken up by their rival, Lorenzo Sonzogno, who arranged the first performance in neutral Monaco. The composer continued to work at revising this, the least known of his mature operas, until his death.

La rondine was initially conceived as an operetta, but Puccini eliminated spoken dialogue, rendering the work closer in form to an opera. A modern reviewer described La rondine as "a continuous fabric of lilting waltz tunes, catchy pop-styled melodies,

and nostalgic love music," while characterizing the plot as recycling characters and incidents from works like 'La traviata' and 'Die Fledermaus'.

Il trittico: Il tabarro, Suor Angelica, and Gianni Schicchi

In 1918, Il trittico

premiered in New York. This work is composed of three one-act operas,

each concerning the concealment of a death: a horrific episode (Il tabarro) in the style of the Parisian Grand Guignol, a sentimental tragedy (Suor Angelica), and a comedy (Gianni Schicchi).

Turandot

Turandot, Puccini's final opera, was left unfinished, and the last two scenes were completed by Franco Alfano based on the composer's sketches. The libretto for Turandot was based on a play of the same name by Carlo Gozzi. The music of the opera is heavily inflected with pentatonic motifs, intended to produce an Asiatic flavor to the music. Turandot contains a number of memorable stand-alone arias, among them Nessun dorma.

Death

A chain smoker of Toscano cigars and cigarettes, Puccini began to complain of chronic sore throats towards the end of 1923. A diagnosis of throat cancer led his doctors to recommend a new and experimental radiation therapy treatment, which was being offered in Brussels. Puccini and his wife never knew how serious the cancer was, as the news was revealed only to his son.

Puccini died in Brussels on 29 November 1924, aged 65, from complications after the treatment; uncontrolled bleeding led to a heart attack the day after surgery. News of his death reached Rome during a performance of La bohème. The opera was immediately stopped, and the orchestra played Chopin's Funeral March for the stunned audience.

A chain smoker of Toscano cigars and cigarettes, Puccini began to complain of chronic sore throats towards the end of 1923. A diagnosis of throat cancer led his doctors to recommend a new and experimental radiation therapy treatment, which was being offered in Brussels. Puccini and his wife never knew how serious the cancer was, as the news was revealed only to his son.

Puccini died in Brussels on 29 November 1924, aged 65, from complications after the treatment; uncontrolled bleeding led to a heart attack the day after surgery. News of his death reached Rome during a performance of La bohème. The opera was immediately stopped, and the orchestra played Chopin's Funeral March for the stunned audience.

He was buried in Milan, in Toscanini's family tomb, but that was always intended as a temporary measure. In 1926 his son arranged for the transfer of his father's remains to a specially created chapel inside the Puccini villa at Torre del Lago.

Most broadly, Puccini wrote in the style of the late-Romantic period of classical music (see Romantic music). Music historians also refer to Puccini as a component of the giovane scuola ("young school"), a cohort of composers who came onto the Italian operatic scene as Verdi's career came to an end, such as Mascagni, Leoncavallo, and others mentioned below.

Puccini is also frequently referred to as a verismo composer.

In opera, verismo (Italian for "realism", from vero, meaning "true") was a post-Romantic operatic tradition associated with Italian composers such as Pietro Mascagni, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Umberto Giordano, Francesco Cilea and Giacomo Puccini.

Verismo as an operatic genre had its origins in an Italian literary movement of the same name. This was in turn related to the international literary movement of naturalism as practiced by Émile Zola and others. Like naturalism, the verismo literary movement sought to portray the world with greater realism. In so doing, Italian verismo authors such as Giovanni Verga wrote about subject matter, such as the lives of the poor, that had not generally been seen as a fit subject for literature.

Puccini's career extended from the end of the Romantic period into the modern period. He consciously attempted to 'update' his style to keep pace with new trends, but did not attempt to fully adopt a modern style. One critic, Anthony Davis has stated: "Loyalty toward nineteenth-century Italian-opera traditions and, more generally, toward the musical language of his Tuscan heritage is one of the clearest features of Puccini's music."[54] Davis also identifies, however, a "stylistic pluralism" in Puccini's work, including influences from "the German symphonic tradition, French harmonic and orchestrational traditions, and, to a lesser extent, aspects of Wagnerian chromaticism". In addition, Puccini frequently sought to introduce music or sounds from outside sources into his operas, such as his use of Chinese folk melodies in Turandot.

All of Puccini's operas have at least one set piece for a lead singer that is separate enough from its surroundings that it can be treated as a distinct aria, and most of his works have several of these. At the same time, Puccini's work continued the trend away from operas constructed from a series of set pieces, and instead used a more "through-composed" or integrated construction. His works are strongly melodic. In orchestration, Puccini frequently doubled the vocal line in unison or at octaves in order to emphasize and strengthen the melodic line.

Verismo is a style of Italian opera that began in 1890 with the first performance of Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana, peaked in the early 1900s, and lingered into the 1920s. The style is distinguished by realistic – sometimes sordid or violent – depictions of everyday life, especially the life of the contemporary lower classes. It by and large rejects the historical or mythical subjects associated with Romanticism. Cavalleria rusticana, Pagliacci, and Andrea Chénier are uniformly considered to be verismo operas. Puccini's career as a composer is almost entirely coincident in time with the verismo movement. Only his Le Villi and Edgar preceded Cavalleria rusticana. Some view Puccini as essentially a verismo composer,[56] while others, although acknowledging that he took part in the movement to some degree, do not view him as a "pure" verismo composer.[58] In addition, critics differ as to the degree to which particular operas by Puccini are, or are not, properly described as verismo operas. Two of Puccini's operas, Tosca and Il tabarro, are universally considered to be verismo operas. Puccini scholar Mosco Carner places only two of Puccini's operas other than Tosca and Il tabarro within the verismo school: Madama Butterfly, and La fanciulla del West. Because only three verismo works not by Puccini continue to appear regularly on stage (the aforementioned Cavalleria rusticana, Pagliacci, and Andrea Chénier), Puccini's contribution has had lasting significance to the genre.

Both during his lifetime and in posterity, Puccini's success outstripped other Italian opera composers of his time, and he has been matched in this regard by only a handful of composers in the entire history of opera. Between 2004 and 2018, Puccini ranked third (behind Verdi and Mozart) in the number of performances of his operas worldwide, as surveyed by Operabase. Three of his operas (La bohème, Tosca, and Madame Butterfly) were amongst the 10 most frequently performed operas worldwide.

Gustav Kobbé, the original author of The Complete Opera Book, a standard reference work on opera, wrote in the 1919 edition: "Puccini is considered the most important figure in operatic Italy today, the successor of Verdi, if there is any." Other contemporaries shared this view. Italian opera composers of the generation with whom Puccini was compared included Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945), Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857–1919), Umberto Giordano (1867–1948), Francesco Cilea (1866–1950), Baron Pierantonio Tasca (1858–1934), Gaetano Coronaro (1852–1908), and Alberto Franchetti (1860–1942). Only three composers, and three works, by Italian contemporaries of Puccini appear on the Operabase list of most-performed works: Cavalleria rusticana by Mascagni, Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo, and Andrea Chénier by Umberto Giordano. Kobbé contrasted Puccini's ability to achieve "sustained" success with the failure of Mascagni and Leoncavallo to produce more than merely "one sensationally successful short opera". By the time of Puccini's death in 1924, he had earned $4 million from his works.

Although the popular success of Puccini's work is undeniable, and his mastery of the craft of composition has been consistently recognized, opinion among critics as to the artistic value of his work has always been divided. Grove Music Online described Puccini's strengths as a composer as follows:

Puccini succeeded in mastering the orchestra as no other Italian had done before him, creating new forms by manipulating structures inherited from the great Italian tradition, loading them with bold harmonic progressions which had little or nothing to do with what was happening then in Italy, though they were in step with the work of French, Austrian and German colleagues.

In his work on Puccini, Julian Budden describes Puccini as a gifted and original composer, noting the innovation hidden in the popularity of works such as "Che gelida manina". He describes the aria in musical terms (the signature embedded in the harmony for example), and points out that its structure was rather unheard of at the time, having three distinct musical paragraphs that nonetheless form a complete and coherent whole. This gumption in musical experimentation was the essence of Puccini's style, as evidenced in his diverse settings and use of the motif to express ideas beyond those in the story and text.

Puccini has, however, consistently been the target of condescension by some music critics who find his music insufficiently sophisticated or difficult. Some have explicitly condemned his efforts to please his audience, such as this contemporary Italian critic:

He willingly stops himself at minor genius, stroking the taste of the public ... obstinately shunning too-daring innovation ... A little heroism, but not taken to great heights; a little bit of veristic comedy, but brief; a lot of sentiment and romantic idyll: this is the recipe in which he finds happiness. ([E]gli si arresta volentieri alla piccola genialità, accarezzando il gusto del pubblico ... rifuggendo ostinato dalle troppo ardite innovazioni. ... Un po' di eroismo, ma non spinto a grandi altezze, un po' di commedia verista, ma breve; molto idillio sentimentale e romantico: ecco la ricetta in cui egli compiace.)

Budden attempted to explain the paradox of Puccini's immense popular success and technical mastery on the one hand, and the relative disregard in which his work has been held by academics:

No composer communicates more directly with an audience than Puccini. Indeed, for many years he has remained a victim of his own popularity; hence the resistance to his music in academic circles. Be it remembered, however, that Verdi's melodies were once dismissed as barrel-organ fodder. The truth is that music that appeals immediately to a public becomes subject to bad imitation, which can cast a murky shadow over the original. So long as counterfeit Puccinian melody dominated the world of sentimental operetta, many found it difficult to come to terms with the genuine article. Now that the current coin of light music has changed, the composer admired by Schoenberg, Ravel, and Stravinsky can be seen to emerge in his full stature.

- Le Villi, libretto by Ferdinando Fontana (in one act – premiered at the Teatro Dal Verme, 31 May 1884)

- Edgar, libretto by Ferdinando Fontana (in four acts – premiered at La Scala, 21 April 1889)

- Manon Lescaut, libretto by Luigi Illica, Marco Praga and Domenico Oliva (in four acts – premiered at the Teatro Regio, 1 February 1893)

- La bohème, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa (in four acts – premiered at the Teatro Regio, 1 February 1896)

- Tosca, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa (in three acts – premiered at the Teatro Costanzi, 14 January 1900)

- Madama Butterfly, libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa (in two acts – premiered at La Scala, 17 February 1904)

- La fanciulla del West, libretto by Guelfo Civinini and Carlo Zangarini (in three acts – premiered at the Metropolitan Opera, 10 December 1910)

- La rondine, libretto by Giuseppe Adami (in three acts – premiered at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, 27 March 1917)

- Il trittico (premiered at the Metropolitan Opera, 14 December 1918)

- Il tabarro, libretto by Giuseppe Adami

- Suor Angelica, libretto by Giovacchino Forzano

- Gianni Schicchi, libretto by Giovacchino Forzano

- Turandot, libretto by Renato Simoni and Giuseppe Adami (in three acts – incomplete at the time of Puccini's death, completed by Franco Alfano: premiered at La Scala, 25 April 1926)

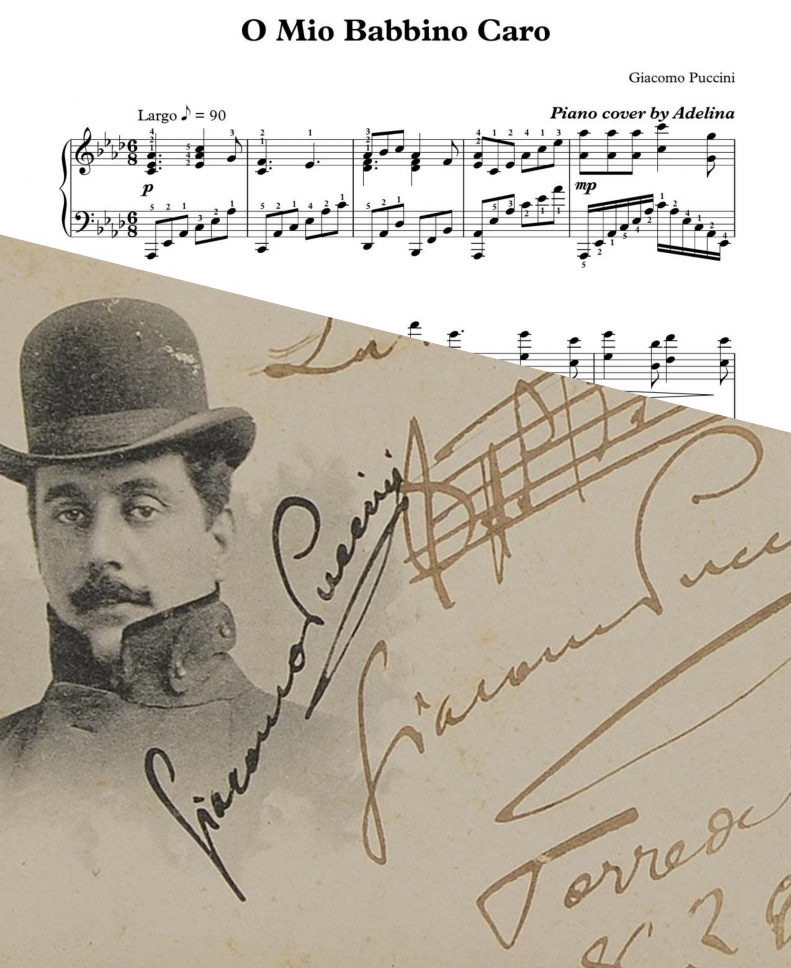

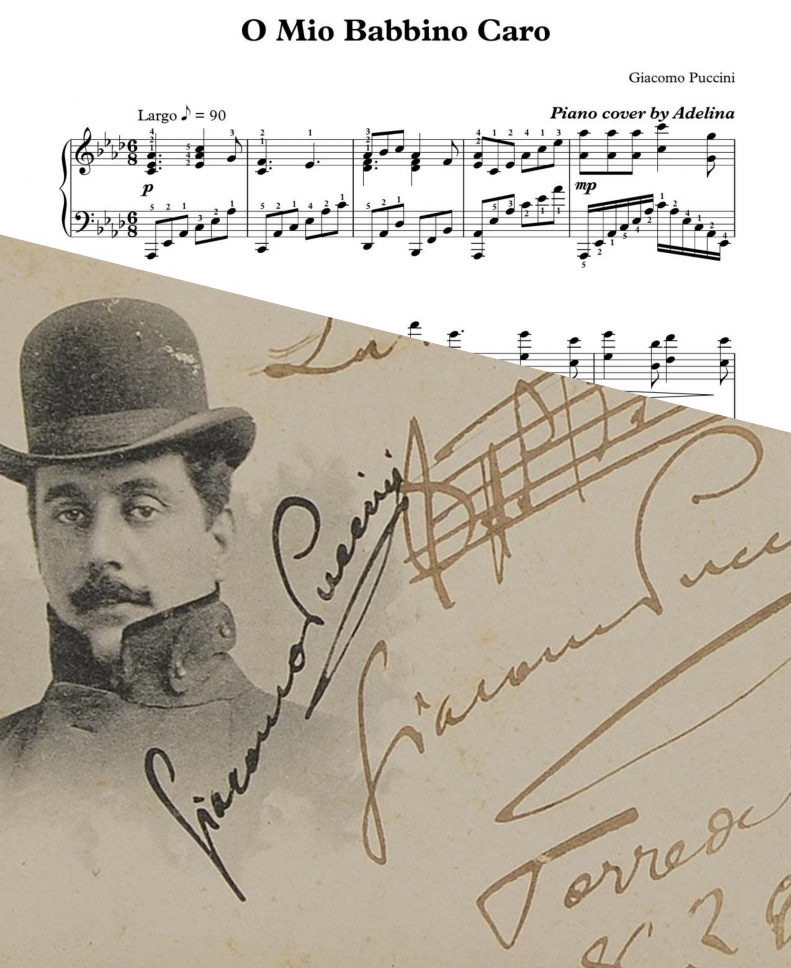

‘O mio babbino caro’

It’s a well-known aria from a not-particularly-famous opera.

From Puccini’s one-act opera Gianni Schicchi (1918), ‘O mio babbino caro’ is one of the most performed arias of the last 100 years.

The

opera itself (Gianni Schicchi) might not have quite the same status as some of Puccini’s other operas – like La bohème (1896) or Tosca (1899) – but its famous

aria continues to secure its place in opera houses around the world.

It provides an interlude expressing lyrical simplicity and love in contrast with the atmosphere of hypocrisy, jealousy, double-dealing, and feuding in medieval Florence.

😦😏

This toddler ugly-crying to ‘O mio babbino caro’ is 😒. The footage, shot in Linköping, Sweden in August 2016, shows the boy bursting into tears as he listens to Puccini's aria "O mio babbino caro." https://www.classicfm.com/composers/puccini/toddler-cries-o-mio-babbino-caro/

This toddler ugly-crying to ‘O mio babbino caro’ is 😒. The footage, shot in Linköping, Sweden in August 2016, shows the boy bursting into tears as he listens to Puccini's aria "O mio babbino caro." https://www.classicfm.com/composers/puccini/toddler-cries-o-mio-babbino-caro/

👇♪ 📽 ♪ 👇

Who sings ‘O mio babbino caro’?

‘O mio babbino caro’ translates as ‘Oh my dear papa’, and it is sung by Lauretta, who begs her father Gianni Schicchi to help her marry the love of her life, Rinuccio.

The aria has famously been performed by sopranos Anna Netrebko, Dame Kiri te Kanawa, Montserrat Caballé and Katherine Jenkins.

What is Gianni Schicchi?

Gianni Schicchi is a short, one-act opera, and the third and final installment of Puccini’s Il trittico (The Triptych).

The Triptych contains three one-act operas, which were initially supposed to be presented together. However, when the Triptych was first performed at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in December 1918, it was clear Gianni Schicchi was the favorite.

Pronounced JA-KNEE SKI-KEE, the opera is based on an incident mentioned in Dante’s Inferno.

In the first part of his Divina Commedia, Dante visits the Circle of Impersonators and sees a man, Gianni Schicchi, being condemned to hell for impersonating Buoso Donati and falsely altering his will.

Staying true to Dante’s story, Puccini’s opera recounts the story of Schicchi, who impersonates the late aristocrat Donati and dictates a new will in his own favour.

Initially,

Puccini opposed the idea of staging Gianni Schicchi outside of the original Triptych, but by 1920 he reluctantly consented to separate performances. Now, the opera is often staged alone, or with other short operas.

No comments:

Post a Comment